The Sporting Hawks of Japan

Most of the hawks trained in Japan are of the same species as those employed by falconers in Europe and North America. Being powerful fliers, raptors have wide geographic ranges, and a few species occur throughout the Holarctic Region. The peregrine (Falco peregrinus), the merlin (Falco columbarius), and the goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) breed in Eurasia as well as in North America. They differ slightly in size and color from one region to another, but their roles in hawking are the same. The hobby (Falco subbuteo) and the sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) are found both in Europe and in Japan. Japanese falconers train two additional species, which are not known in western Europe and North America: the diminutive Besra sparrowhawk (Accipiter virgatus) and a large, powerful hawk-eagle (Spizaetus nipalensis). The Besra sparrowhawk has never been a popular bird in Japanese hawking, but the hawk-eagle has been used for hunting hares in the mountains since the Tokugawa Period (seventeenth century) or before.

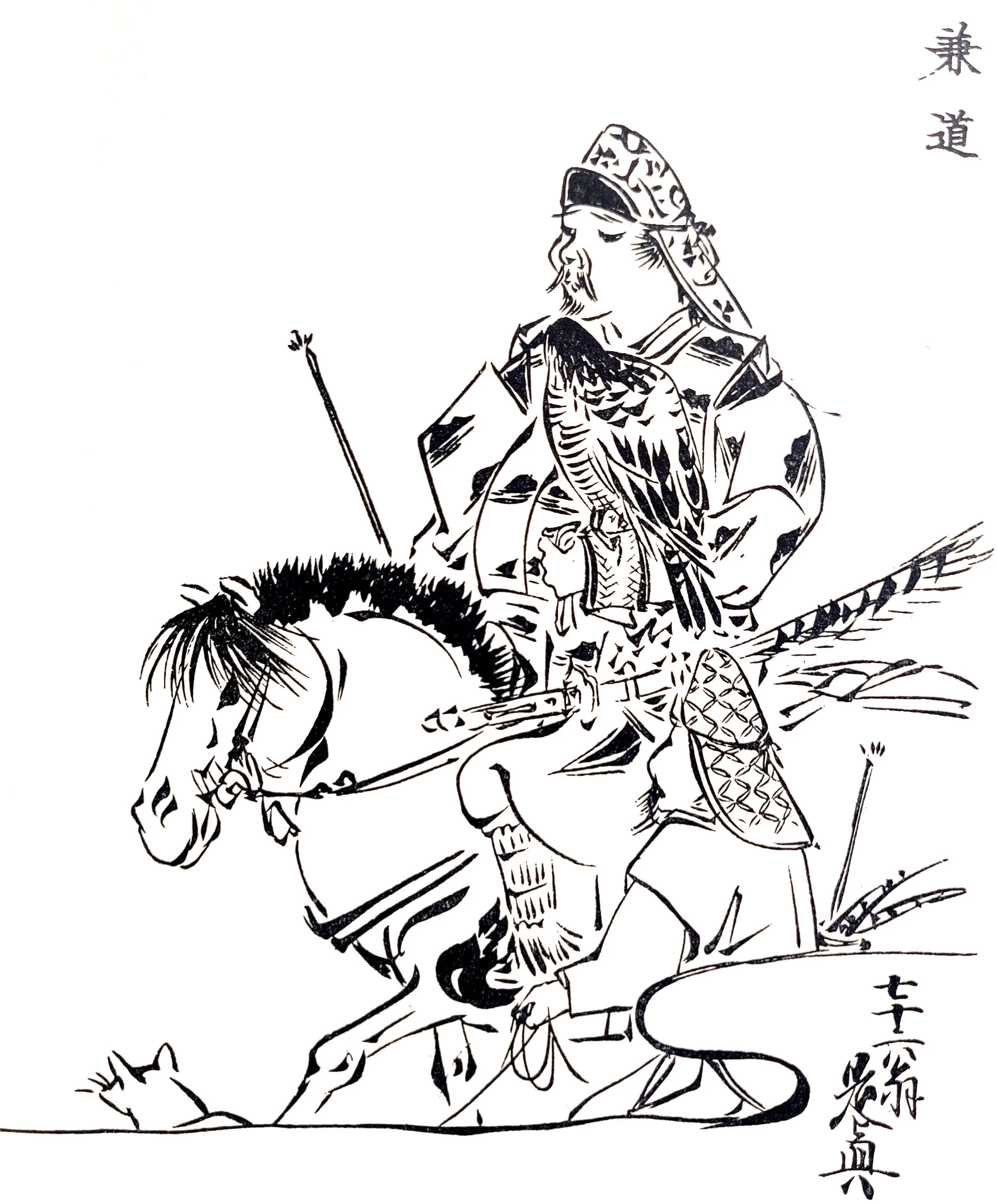

Adult Japanese goshawks (Accipiter gentilis). Left, male, owned by Mr. Arie Niwa (showing typical leash and muchi). Right, female, owned by Dr. Masaki Sano. The difference in the ventral barrings is probably an individual variation.

The classic hunting hawk in Japan, as in China and Korea, has always been the goshawk. In a country where there are many hills and forests, it is natural that short-winged hawks should receive more attention. A goshawk is of the proper size and strength to capture the most common quarry; pheasants and hares. In Japan the goshawk is called otaka; taka is a generic term for hawk, and in otaka the o is accented and means large or great. Otaka is sometimes translated as "honorable hawk" and in this case the syllables are unaccented. This is not, however, a correct translation of the Kanji or Chinese ideograph. Falconers in the past also employed the name godaka for the goshawk and this also means honorable hawk. Another old name for the goshawk is aodaka meaning blue hawk, in reference to the blue or gray color of the adult. This is the literal translation of the ideograph and the abbreviated pronunciation of aodaka is otaka.

When hawking was first introduced to Japan, trained goshawks, falconers, and books were brought from Korea. In the autumn, goshawks migrate southward through the Korean Peninsula and, in the past, were netted and annually sent to Japan in large numbers. The Japanese goshawk (Accipiter gentilis fujiyamae) is smaller and darker than those (A. g. schvedowi and A. g. albidus) which are trapped in Korea and the latter two are undoubtedly more powerful hunters. The goshawks that breed in Hokkaido are said to be larger than those from Honshu, but ornithologists do not agree on the correct subspecific name for these northern birds. In all likelihood, the large A. g. schvedowi enters Hokkaido at least in the autumn and winter.

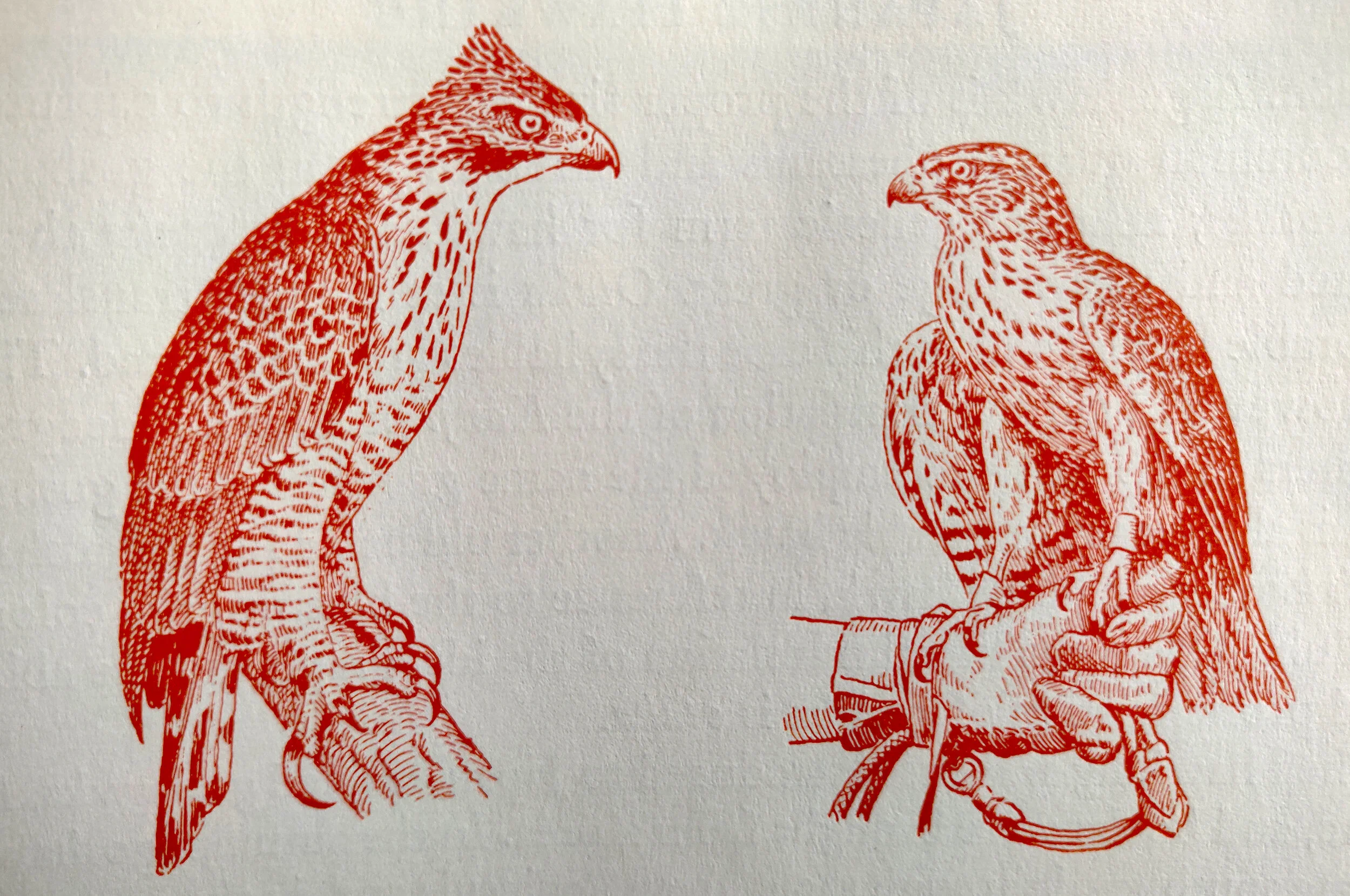

Adult sparrowhawks. Left, Besra sparrowhawk (Accipiter virgatus). Right, Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus). Both birds of Dr. Masaki Sano.

There are two species of sparrowhawks in Japan and both are useful hunting hawks. The Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) is called haitaka (ashy hawk) because the dorsum in grayish, especially in the male. In earlier days it was also called hasbidaka, but the meaning of this name is obscure. The male is called konori. This species was occasionally used in hunting and is sometimes trained today for it is still commonly taken by netters and can be purchased in bird shops. The Eurasian sparrowhawk is rather common in forested areas of Japan, and has occasionally been found nesting in Honshu. Wild sparrowhawks in Japan feed mostly on small birds. Contrary to popular notion, the Eurasian sparrowhawk is not very similar to the Nearctic sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus). A. nisus is larger, the beak is relatively larger, and the shoulders are broader. Also, immature individuals of A. nisus are horizontally barred below and in A. striatus the breast plumage of the first-year birds is vertically streaked. The Besra sparrowhawk (Accipiter virgatus) occurs in eastern and southern Asia and nests in Japan, at least on Honshu. This species is called tsumi (for the female) and essai (for the male); another name, suzumetaka (lit., sparrowhawk), was once used. The fact that there are old Japanese names for this little hawk suggests that it was distinguished from the haitaka since ancient times. A. virgatus is smaller than A. nisus and, in many ways, resembles the sharp-shinned hawk (A. striatus) of North America. The size and form, and the plumages of both the adult and immature A. virgatus and A. striatus are very similar. Because the dieting of these small hawks is so difficult, sparrowhawks have never received as much attention from austringers as has the hardy goshawk. Neglected by the nobility, the active little hawks were trained by rural falconers. Trained sparrowhawks usually captured skylarks and quail, but strong females were known to have taken ducks as large as mallards. Very little is known about the care of these small hawks but, except for the more carefully adjusted feeding, the training methods are about the same as for goshawks.

Adult Japanese hawk-eagles (Spizaetus nipalensis). Left, female, owned by Dr. Masaki Sano. Right, male, owned by Mr. Toshio Tomita. Both birds in dark (normal) color phase. Note small crest of male.

A hawk-eagle (Spizaetus nipalensis) is trained for hunting in the northern mountainous regions of Honshu, especially in Yamagata and Akita Prefectures. The same species has been flown in Korea and China, at least until very recently, and the methods for handling this large bird were probably brought from Korea to Japan many centuries ago. The Japanese hawk-eagle is called kumataka (lit. bear-hawk) perhaps because of its rather fierce appearance. It is the largest raptor regularly trained in Japan and most falconers believe that the kumataka is too large and slow to capture birds. Although it is not a fast bird, it is very powerful. It can kill a hare (Lepus brachyurus) with apparently little exertion and trained birds occasionally take foxes, raccoon dogs, and marten. On snow-covered hillsides, low vegetation is buried and mammalian game cannot run rapidly; under such conditions, a hawk-eagle is a very appropriate subject for an austringer. This species of Spizaetus occurs from south-eastern Asia north to Korea and Japan and though it is not abundant, it breeds in forests of high mountains on the four main islands of Japan.

In general aspect male and female hawk-eagles are rather similar, the main difference being that of size. As in other raptorial birds, males are considerably smaller than females. A female may weigh as much as three and a half kilograms or more and males usually weigh about two and a half kilograms. The wingspread of a large female may be as great as two meters. In males the hind claw bears a small straight groove and there is a crest of two feathers that project slightly beyond the contour of the crown. The crest of the male, though conspicuous, is less developed than in most other hawk-eagles. These features are evident in male nestlings, even in the downy stage. The eyes of very young kumataka are blueish gray. Gradually they become lighter and when the hawk-eagle is two years old, its eyes are yellow. In time the color deepens and at five years it is a rich golden yellow. The beak and cere are dark and do not change color with age.

Immature hawk-eagles differ somewhat from adults in color, the white underwing coverts being a characteristic feature of young birds. Two years are required to complete the first molt but the change in appearance is not great. In individuals about ten years old, the facial and head feathers are dark and, at first glance, the head plumage resembles that of a golden eagle. Some hawk-eagles are extremely pale on the breast, but dorsally about he same as the more common dark plumaged birds. In Japan about ten per cent of the hawk-eagles are of the light color phase. The foot of these birds is especially important, as in all raptors, and deserves consideration. The inner toe and hind toe are very thick and strong and are the most important when the hawk is binding to game. The middle toe is moderately long, but the outer toe is relatively small and unimportant. The claws or talons are developed in proportion to the size of the toes. The tarsus is feathered as far as the foot, but the toes are nude.

Mr. Asaji Kutzuzawa provided us with the following first-hand report on the habits of these birds.

"The wild kumataka is a creature of remote forests and high mountains. In central and northern Honshu these birds nest at elevations from about eight hundred meters in open forests of tall straight trees. Hawk-eagles forage to a distance of about four kilometers from their nest and drive out other hawk-eagles that happen to trespass in their territory. The nest is usually from ten to twenty meters above the ground in a tree which has large thick branches near the top. A pair remains mated for life and every year returns to one of two or three old nests, adding to the structures so that they eventually may exceed two meters in width and one meter in height. In early March these nests can be seen from a great distance. If a young hawk is removed or if adults are disturbed, the nest will be deserted and the same pair will use another nest nearby.

"In the Tohoku District (northern Honshu) of Japan, a single egg is laid about the twentieth of April. The egg is about twice as large as that of a chicken, more or less round, and white with a reddish tinge. Only the female broods the egg and during this period the male hunts for himself and his mate. He exhibits great concern for the welfare of the nest and its occupants and defends them against intruders. After an incubation period of from twenty-eight to thirty days, the female continues to remain at the nest and huddles over the downy chick. The male is still the hunter, but he gives quarry to the mother, who tears the food into small bits and gently presents it to the fragile infant.

"At the end of June the young is able to fly from the nest, but throughout the summer the family remains together. In early autumn both parents and young can be seen circling high over the forested ridges and the 'peee, pee' of the hungry offspring can be heard from a great distance. The youngster is still under care of its parents and in mid-September the adults can be observed teaching it to hunt. One of the parents carries a hare or some other game high in the air, above where the young hawk-eagle is perched. The parent drops the food and the youngster seizes it on the ground. By continued lessons of this sort, the beginner learns to expect food on the ground. Gradually it becomes independent of its parents.

"Wild hawk-eagles eat a variety of medium-sized birds and mammals: hares, squirrels, coots, and pheasants form the bulk of their fare. These hawks usually hunt in the morning and, if a bird is not successful, it will hunt again in the latter part of the afternoon. Much of the hunting is done from the air and when prey is sighted, the kumataka dives and captures it by surprise on or near the ground. If the quarry escapes, the hawk sits in a nearby tree and waits for it to reappear. If it is successful, it will gorge itself and may not hunt again for ten days.

"In captivity these large hawks are very long-lived and some live for twenty-five or thirty years. As they become older, their flight becomes slightly altered. At seven or eight years they hold their wings slightly above the level of their bodies, but later the wings are horizontal when gliding. When an individual reaches twenty years of age, its wings are somewhat bowed in flight."

Falcons, or long-winged hawks, have been less popular in Japan than the short-winged species. There are relatively few Japanese paintings of trained falcons and the literature is less precise regarding methods by which they were handled. Even now, there are not many localities in which falcons can be flown with success and in the past, when Japan was more heavily wooded, there must have been very few places where long-wings could be kept in sight. As in Europe, peregrines and merlins were the falcons most often used for hunting. The peregrine (hayabusa, or swift-tuft hawk) nests along the coasts of Japan and in favored sites in the interior mountains. Several subspecies occur in the autumn and winter months, evidence that falcons enter Japan from other regions. The breeding bird is Falco peregrimus japonensis and F. p. harterti comes to Japan from the continent to the north. The Peale's falcon (F. peregrinus pealei) has been reported from Quelpart Island (between Kyushu and Korea) and a Peale's falcon, presumably netted in the Inland Sea of Japan, was given to us in the autumn of 1958. In addition, P. p. fruitii, from the Volcano Islands, has been collected on the Islands of Izu (south of Tokyo). These records (from A Hand-List of the Japanese Birds, 4th ed., 1958) indicate the heterogeneity of the peregrine population of Japan.

Passage falcons are trapped in the autumn and there is no mention of eyass falcons having trained in Japan. Peregrines were employed as game hawks and were also flown from the fist in the manner of hunting with short-winged hawks. Most falconers in Japan insist that the peregrine is a rather inferior bird and cannot be used for more than a single season, but in a conversation, Mr. Arie Niwa of Nagoya stated that this is simply an old wives' tale and that he has flown several peregrines each for several successive seasons.

The merlin migrates south to Japan in the winter but it is not known to nest in Japan. According to ornithologists, this little falcon follows the migrating shore birds and was presumably taken by professional bird netters in the past. There are some old paintings of trained merlins, but it was never as popular as in Europe. The hobby (Falco subbuteo) occurs in Japan and nests in Hokkaido. Japanese falconers apparently do not hunt with the hobby for there are no references to it in either recent or old hawking literature.