Methods of Obtaining Hawks

Japanese falconers train both wild-caught hawks and eyasses, according to the quarry for which the birds were to be trained and, naturally, according to which hawks are more easily obtained. An eyass is sudaka or sutaka (lit., nest-hawk), a passager is agake or akage (aka meaning red, referring to the plumage; or aki, meaning autumn), and a haggard is toyadaka (toya is the building in which hawks are housed, but the significance is not apparent).

In the mountain forests of Honshu eyass goshawks were taken, and ancient illustrations show the partly feathered young being removed from the nest and placed in a basket. Other old drawings depict different types of nets used to capture goshawks and falcons in the autumn and winter months. As a rule, eyass goshawks were necessary for hunting geese and cranes because the wild-reared hawks had learned to avoid these powerful and clannish quarry. Today hawking for geese and cranes in Japan is only history, and now passage hawks are generally preferred for the smaller quarry that remain available to modern falconers.

Among the wild-caught birds, passage hawks are considered to be more tractable because the old haggards, having hunted for themselves for several seasons or even years, have learned many individual traits and do not always willingly pursue quarry according to the wishes of the falconer. In contrast to eyasses, passage hawks are quiet and are free of the foolish vices which are found in the generally neurotic eyass hawks. Even when well trained, the passage hawk or haggard will always retain some of its wild nature and never be as close to its trainer as the eyass; for this reason, in reclaiming his newly-caught bird, the falconer must have not only spirit and enthusiasm, but must exhibit the utmost gentleness and kindness. In spite of the difficulty of overcoming the proud and independent nature of the wild-trapped bird, the falconer is well rewarded for his greater effort, for through experience these birds have developed their techniques for maneuvering and hunting, and frequently turn out to be superior to the eyasses. The wild-caught bird may have its favorite quarry or a certain position for attack. In manning and training a haggard or passager, the falconer should be especially sensitive to any eccentricities his bird may exhibit, and later, when hunting, he should take advantage of his bird's individual talents.

In both goshawks and hawk-eagles, there is a wide gulf between the behavior of the eyass and the wild-caught haggard or passage hawk. The eyass is, of course, very tame and is virtually a child of the falconer. Generally its flight is inferior to the speed and dexterity of the wild-reared hawk and the eyass hawk-eagle is not as quick to dive at the rabbit lure. When eating or when hungry, the eyass is apt to be noisy, and in the field the falconer may frequently locate his bird by listening for its voice. By contrast, the passage hawk and haggard are quite silent at all times.

During November and December many immature goshawks move down from the mountains, following other birds. At lower elevations, trappers set their nets in open meadows where the bait will be seen from a long distance. The nets are the same as described below for capturing hawk-eagles, but for goshawks, pigeons are the customary bait.

Passage hawks (goshawks) are usually trapped in November or December when they appear at lower elevations. In the autumn and winter months, hawks are occasionally trapped at commercial duck ponds where waterfowl come to feed and rest. These ponds are maintained solely for water birds, and they are baited to attract ducks which are netted for both sport and food. The ducks are fed from tightly built blinds or hides and are seldom far from their source of food. Through a sloping bamboo pipe, a caretaker can provide grain for the ducks, and through a pinhole in the blind, observe their activity. Passage goshawks taken at this time are better fliers and footers than eyasses but are still rather docile when compared to haggards. As elsewhere, females are valued above males, but in Japan the difference is not considered to be so important. In Japan the hare (Lepus brachyurus) is not especially large, and can be taken by both male and female goshawks; moreover, males are satisfactory for pheasants, ducks, and coots. If a goshawk is known to be in the vicinity, it is a simple matter for the caretaker to become a hawk-trapper; by pushing a teal through the reeds in the roof of the blind, he is almost certain to attract the nearby gos and, when the hawk attacks, the trapper can easily grab the bird's feet. Falcons frequent these duck ponds in the winter and are sometimes captured in the same manner.

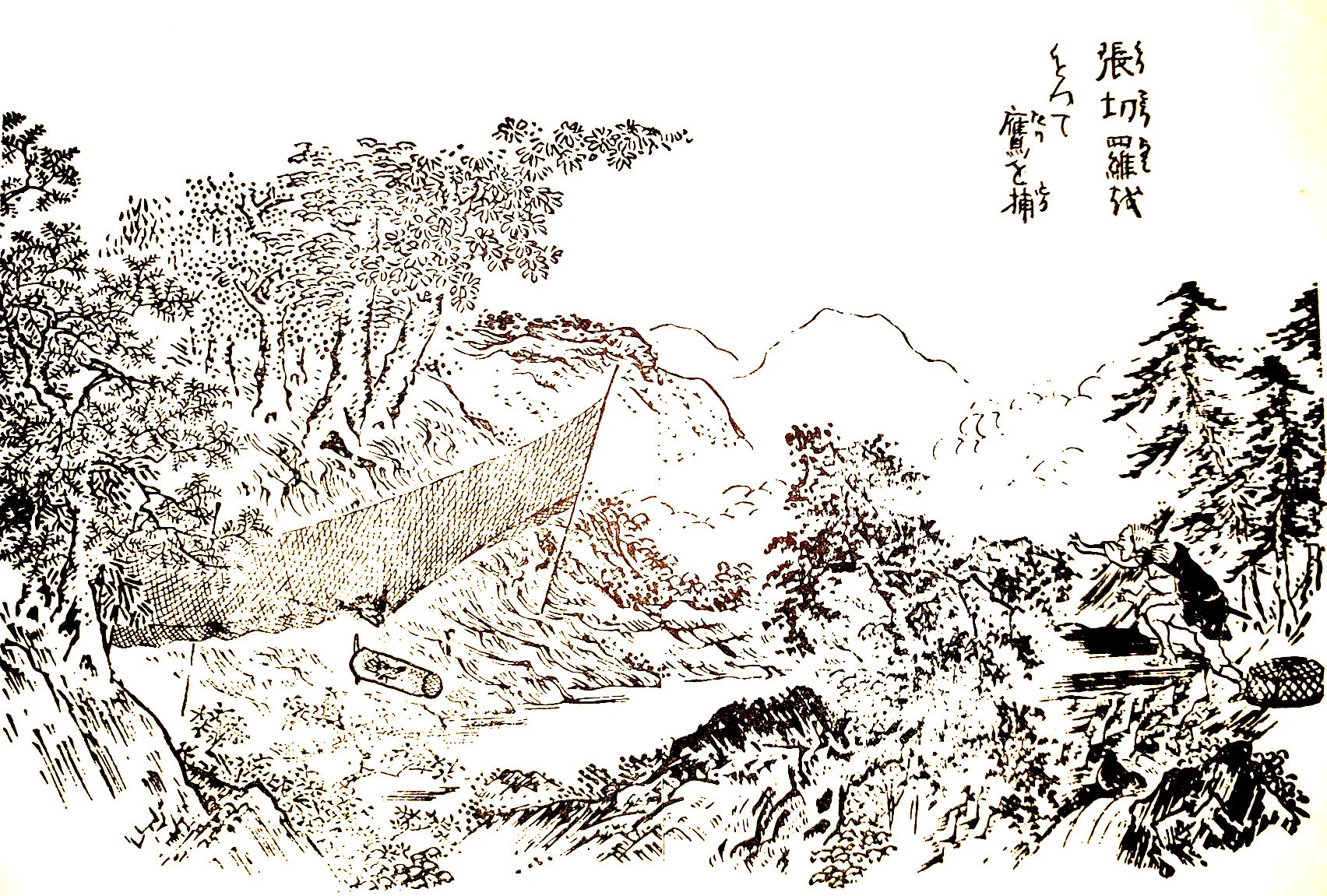

Kimoura (1799) described the capture of sparrowhawks (Accipiter nisus). Haitaka, or, as Kimoura termed them, hashidaka, were netted in July and August in the mountains of Shikoku, and the same process was probably employed elsewhere. The net is set up in somewhat the same manner as the dho-gaza (or do-guz) of the Middle East, but, in contrast, the end poles are planted firmly in the ground and do not fall as the hawk hits the net. This type of net is called kiri-ami (ami means net, but the meaning of kiri in this case is not clear). The mesh is 1½ to 2½ inches. The net is from 3½ to 4½ feet high and about 14 feet long and supported at each end by a highly polished and lacquered bamboo pole. On the ground, midway between the ends of the net, is a bait cage, chôchin-ami (lit., lantern net), about a foot in diameter and cage, 3½ to 4 feet long. Usually a bulbul (Ixos amaurotis) serves as bait. By means of a light string running from the bait to the trapper's site, the hawk-trapper is able to make the bulbul flutter when the hashidaka comes into view.

The kiri-ami is set up at night and the trapper begins his watch before dawn, as the hawks start to hunt before sunrise. When a hawk approaches the net, the line to the chôchin-ami is pulled, and the flapping of the bulbul is certain to attract the small raptor into the net. As it hits the net, the ends move along the smooth poles, forming a bag about the hawlk. This is illustrated in MacPherson (1897: 202) and the same drawing is in Boyer and Planiol (1948: 236).

Immediately, the little hawk is equipped with jesses and a leash, and the tail is wrapped with paper to protect the long delicate feathers. The freshly-caught hawk is transported in a smaller basket (fusego)

Hawk-eagles and goshawks are sometimes captured by an arrangement of three or four nets. The netting is made of cotton thread about one-eighth of an inch in diameter, dyed dark brown. The mesh is about 2½ to 3 inches and each net is about seven feet square. On the upper and lower margins are tied metal rings, about one inch in diameter; and at each corner is a short section of bamboo, about one inch in diameter and four inches long.

The four nets are hung to form a square; a pole is planted firmly in the ground at each corner, each pole projecting about seven feet above the ground. Connecting adjacent poles is a waxed cord at both the tops and the bottoms (about six inches above the ground) and the waxed cords run through the rings, supporting the nets. The cords are rather taut, but the distance between the top and the bottom cords is less than the height of the net, so that the net hangs loosely. Each corner of the net is held insecurely to the nearest pole by the bamboo section which is placed over a stump or projection on the pole. The pressure of a large hawk hitting one of the four nets is sufficient to pull the two bamboo sections away from the poles and, as the rings slide along the waxed cords toward the hawk, the bird is enveloped in a huge bag. Some falconers attach the nets only by the corners; a small weight tied to the corner is held in the crack of a split wooden peg which is in turn held to the pole. The weights pull out from the pegs when the hawk hits the net, and the net closes behind the bird.

For a decoy the trapper uses a pigeon, a hen, or a hare which is placed in the middle of the square; from a harness about the bird, a line runs to the trapper's blind, some fifty feet away. By pulling the string the trapper can raise the bait and cause it to struggle, and hawks are very prompt in noting that the potential prey is encumbered. A similar arrangement of nets has, until recently, been used to trap hawks in Korea.

Hawk-eagles are most easily trapped from November to March for at this time their appetite is strong and their suspicion is correspondingly less. Moreover, at this time of the year the trees are bare and one can locate these large hawks with less difficulty. Only when the winter hunting area of a bird has been discovered should the falconer trouble to erect a blind and a trap. The trap should be placed near a known favorite perch of the hawk-eagle; and, if the trapper has studied the bird's habits carefully, he should net it in the first day.

Goshawks were common nesting birds in many areas until the beginning of the Meiji Period. Fine eyasses (sudaka) were procured in Hokkaido and in the higher elevations of central Honshu, but as gunning became popular and forests were thinned these hawks became less abundant. It is rather likely, also, that they have become secretive with intensified land use and perhaps they are not so scarce as one might suspect.

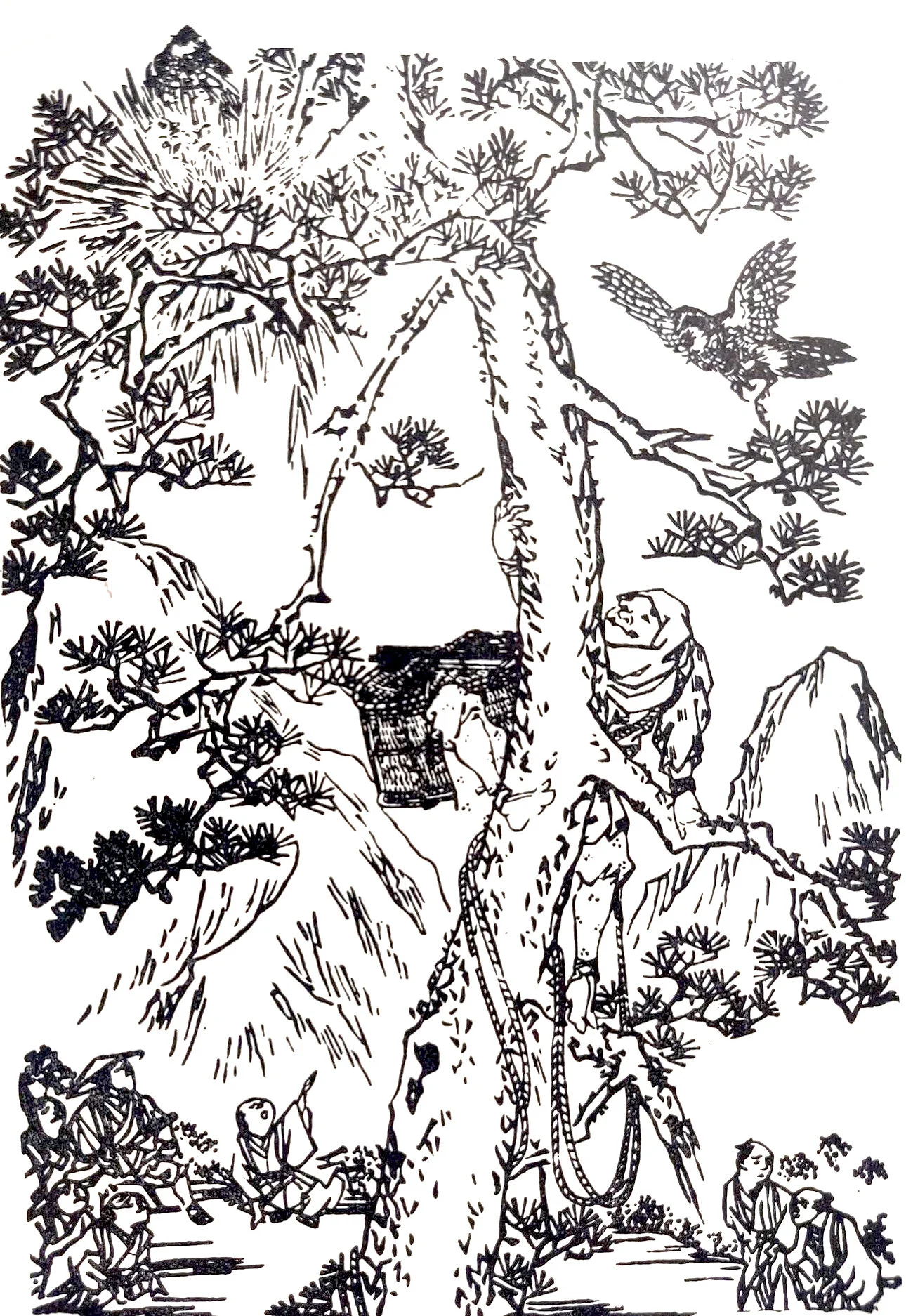

If the falconer proposes to take an eyass, he should begin in March and locate the nest when the new leaves are just beginning to open. In this way he can observe the progress of the nestlings and know exactly when to take his bird. It is possible to take the young hawk at five or six days of age, but young goshawks are usually taken when they are about twenty days old and hawk-eagles when about a week older. When the falconer climbs the nest tree of a pair of hawk-eagles he must be extremely careful for at this time the parents will attack in great anger. Even goshawks can be dangerous and the climber will be wise if he wraps his head and neck loosely with thick cloth. The nestlings are carefully placed in a hamper (fusego) or basket; and when the lid has been securely fastened, the falconer slowly lowers his treasures to a helper below. The young hawk or hawks must be kept as quiet as possible and quickly deposited in an imitation nest in the hawk house. A rabbit skin is used to line the inside of the nest, and on top of the fur are placed the fragrant leaves of mogusa (Artemisia moxa).

The young eyass must be fed generously with the best of tender, fresh meat. Three times a day the voracious child is fed, a total of about one-quarter or one-half pound of food being given daily. Gradually the youngster grows, his plumage develops, and the imitation nest is replaced with a low perch (jiboko). The young hawks are allowed to perch on the jiboko when the third dark bar has appeared on the tail. A mosquito net is placed over the young birds at night. For the next four weeks they exercise their wings and legs, and eat an abundance of fresh meat (good beef and horse meat). When three months old, they are full grown and at this age may be removed from the house, allowed to bathe, and are introduced to initial training.

From time to time, falconers have raised the question of the feasibility of rearing a hawk from an egg. Although this is not to be recommended as a regular procedure, one might wish to attempt it if eggs were in danger from collectors. It seems worthwhile to record the experience of Asaji Kutsuzawa, who took a freshly laid egg from a nest of a hawk-eagle.

"On one occasion I took an egg from a nest and reared the young hawk. The result was satisfactory and it may be of interest to outline the procedure. When the falconer removes the egg from its original nest, he can keep it warm by placing it inside his shirt until he returns home, at which time it should be placed under an incubating hen. Barring accidents, a newly-laid egg will hatch within 28 or 30 days. The young bird is then placed in a warm nest of cotton or fur and fed blood and ground meat from freshly killed birds about four times a day. This food should be no more than six hours old. When the young hawk is a week old, it will take small pieces of meat, slowly presented with chopsticks; when tapped lightly on the head with the chopsticks, the young bird will open its mouth. The two-week old hawk will take about one ounce of fresh meat per day. When it is three weeks old, it should eat the meat and crushed bones of rats; the rats are first skinned so that the hawk has no casting at this age. A diet of rats can be continued until the bird is about six weeks old, at which time it will have learned to tear food for itself. Gradually the quantity and variety of food can be increased."

In the past, passage falcons were trapped in Ibaraki Prefecture in eastern Honshu and Kagoshima Prefecture in southern Kyushu. They were trapped with bird lime, using a pigeon as a lure. On a migration route, or in a region frequented by falcons, the trapper hid in a blind and nearby tethered a golden plover. The plover acted as a sentinel for it would become alarmed long before the falcon came into view. When the plover announced the falcon's approach, the pigeon was gradually pulled toward a sandbag which was covered with bird lime. The pigeon was kept several feet from the bird lime until the falcon had made its kill at which time the quarry and the hawk were slowly pulled to the sandbag. When the falcon was removed from the sticky sandbag, its feathers were cleansed with a mustard solution which removed all traces of the material.

In the past, falcons were sometimes taken in bow nets. Mr. H. Saito, a famous authority on Japanese dogs, has an old manuscript describing and illustrating the capture of peregrines in the seventeenth century with the same sort of bow net as used by the Dutch. Inasmuch as Dutch traders entered Japan in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it is quite possible that the bow net was introduced directly to Japan from Holland.

In modern times a falconer cannot always trap a passage hawk himself, and must obtain it by any means feasible. Surprisingly, one source of wild-caught hawks are bird shops, of which there are many in all large cities. Despite the legal protection for all hawks in Japan, goshawks and peregrines can sometimes be found in bird shops in the autumn, and other kinds occasionally are offered for sale. The prices are reasonable, varying from 2000 to 4000 yen (in 1958, when the exchange was 360 yen for one U. S. dollar). These birds, although not feather-perfect, are generally intact and in good health, having been taken, usually netted, by professional bird catchers. It is also possible to purchase birds from falconers who live in rural areas, and the prices from range 15,000 to 30,000 yen.