Manning and Training

It is obvious why you have no skill in training hawks: you sleep late in the morning and take a nap in the afternoon

— Arai Tazaemon, 1658.

In manning the newly-taken hawk, the Japanese falconer follows established protocol with deliberation and aplomb, reflecting the Japanese sense of formality and dignity. Skill in training hawks was highly regarded since the earliest days of Japanese hawking. Although the general pattern of manning and training goshawks was rather inflexible, there were several schools and a critical eye could recognize the behavior of birds trained by an especially skilled (or an unusually clumsy) falconer. The falconer prided himself on his control over his bird, and this reached such a degree that if he lost his bird, he was likely to commit hara kiri in front of the witnesses.

Although there are numerous variations in methods of manning and training hawks in Japan, some features are characteristic of, and unique to, hawking in this part of the world. First of all, severe dieting reaches an extreme that would be rarely attempted by western falconers. Secondly, the use of a darkened hawk house, or dark box, seems not, at least until recently, to have been part of the routine in European and American falconry. As is typical of falconers everywhere, everyone has certain techniques which differ slightly from those of his associates, and the methods which we have seen and which have been explained to us are not always the same. To combine all these variations in a sinele explanation would result in a procedure not used by any one person. To avoid this pitfall, we shall describe the method used at the Royal Household and another followed by Mr. Shigehiko Niwa (of Ibaraki Prefecture) for goshawks. That for hawk-eagles is, for the most part, the technique of Mr. Asaji Kutsuzawa. With both eyasses and passagers the patterns are almost the same, differing mainly in degree.

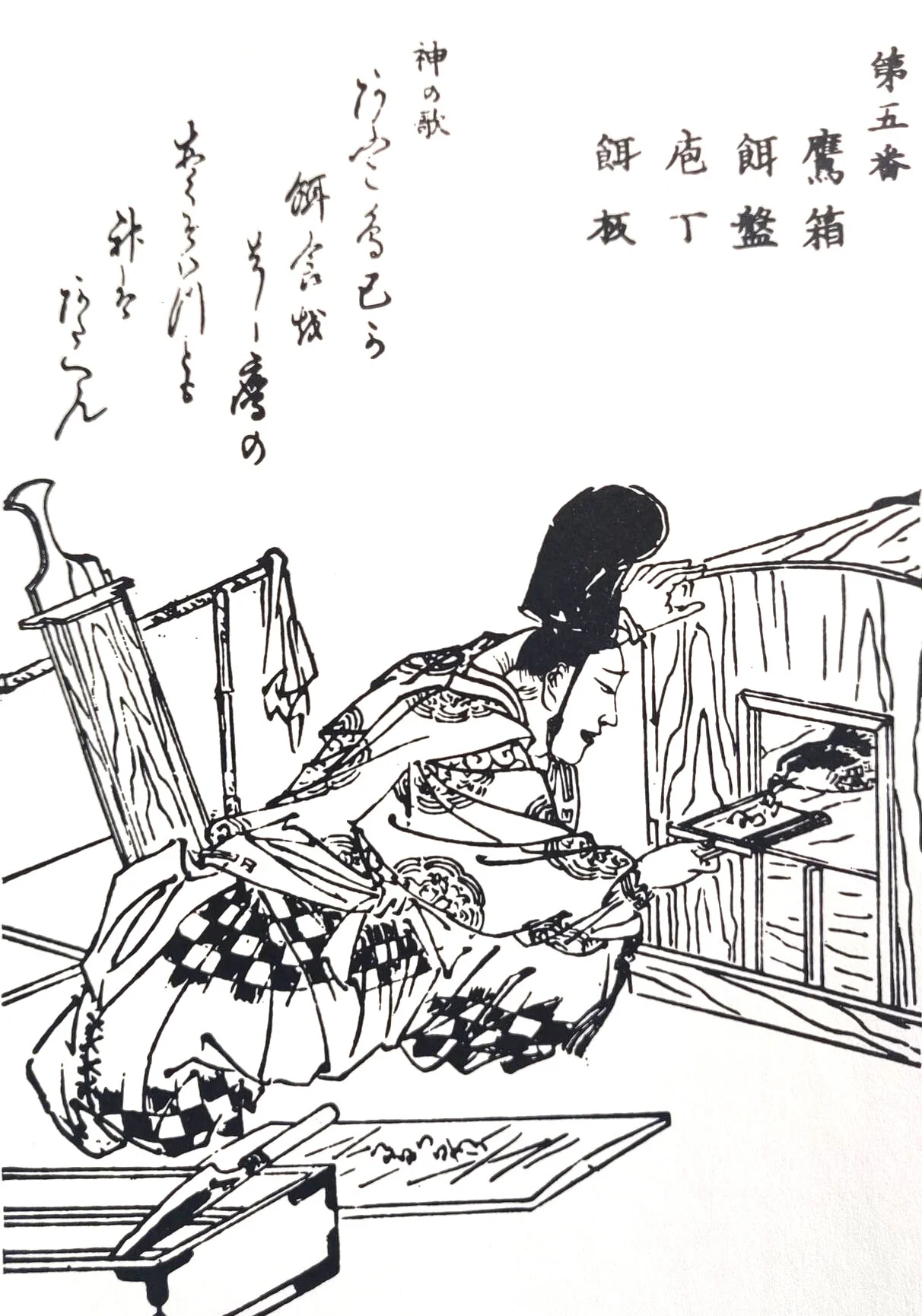

The falconers of the Royal Household follow a method for training goshawks, which is probably very close to the traditional method once used widely in Japan. The following set of instructions was written from conversations with Mr. Toshinaga Bojo and the falconers of the Royal Household. With it are associated the dark room and strict dieting which is known as the Edo-ryu (i.e. Tokyo method).

Immediately after the hawk reaches the falconer, the beak and talons are trimmed. In ancient times a special jacket (fuseginu) was used to hold the wild bird, but today an assistant simply wraps the hawk with a heavy cloth and grasps the bird so that its legs and wings cannot move. The beak and talons are trimmed (coped) with a sharp knife, and if bleeding follows, a hot iron is gently applied to the raw spot. Then, by placing the thumb and index finger between the upper and lower mandibles, one can hold open the mouth and trim the lower mandible, also removing any dry meat from the mouth. New jesses and a leash are attached. While the bird is still being held, any dirt is washed from the feathers with warm water and soap. Should any long shafts be bent, they are dipped into very hot water and straightened. Broken feathers are imped with bamboo. Before the bird is placed in the hawk-house, it is given (force fed) two or three pieces of pigeon meat, washed well for several hours.

The hawk-house floor is cleaned and the bath covered with a piece of wood. If it is cold, about five inches of straw or dried leaves are placed on the floor. The freshly caught hawk is tied to a specially prepared screen perch: the pendent screen is held out both in front and behind at about a forty-five degree angle so that, should the hawk bate, it can easily walk back up the straw screen to the perch.

Feeding is attempted the first night but a stubborn bird may refuse food for two weeks. A pigeon is prepared by removing the head and cutting away the skin from the breast muscles; a pigeon thus prepared is called a maribato. Entering the hawk-house quickly and quietly, and holding the food in the left hand, the falconer offers it to the hawk. This is done by placing the right hand below the left and slowly moving it along the screen perch in the dark until the hawk is felt. He touches the hawk's foot with the pigeon and makes a squeaking sound. If it should begin to eat the first night, it is given just a little breast meat and then left in quiet. If it does not eat, the bird is left alone. Here begins a period during which food is withheld.

The period of starvation may be from one to two weeks, depending upon the season and the condition of the hawk: in winter the bird needs more energy and the starvation period may be three or four days shorter than in the summer. If the food is withheld long enough, the subsequent training is much easier. If possible, this period is scheduled so as to begin at the time of a new moon rather than a full moon. Once a day, open the door slightly to examine the condition of the hawk. After three or four days the mutes will decrease and become green and the hawk's eyes will tend to sink into the head. Although it is best to wait until the bird is rather weak, a mistake at this time can be disastrous. If the bird is judged to be very weak, one should take a pigeon (maribato) prepared as above and repeat the initial feeding. If the hawk attempts to eat, do not feed it, but feel the breast muscles to determine whether or not it is ready to continue training; if the sternum is not projecting sharply from the pectoral muscles, the hawk's condition is not greatly reduced. One should be very cautious at this point because some hawks are rather lean when trapped and cannot tolerate any restriction in feeding. If it is decided to commence manning and feeding, give the hawk a few bites of pigeon and some water; and, after drinking, she will probably rouse. But for the time being, leave the bird alone and check it again the next night. The falconer should remember that water is a laxative, and at this time causes the hawk to lose weight more rapidly. The second night give the bird the prepared pigeon (maribato). While the bird feeds, call "ho-ho" in a low voice and notice whether or not it is alarmed at your voice. Also give some food from the food box; tap the box lightly and then place it above the part of the pigeon on which the hawk is feeding. In this first 24-hour period give one pigeon and allow the hawk to drink and rouse. Note the condition of the breast muscles in order to judge the next day's allowance of food.

On the second night this initial procedure is repeated and, if the hawk is not alarmed, make more noise with the leash and teach the bird to become accustomed to your movements and voice. Allow it to feed on the pigeon, and also take food from the food box (egôshi). As on the first night, note any changes in the breast muscles and repeat the visit on the third night. This time the hawk will know what to expect and if nothing changes, untie the leash and pick up the bird for the first time. Walk about inside the hawk-house, talking to the bird in a low voice, but avoiding any sudden movements that might scare her. If she is quiet, open the door slightly and note her attitude; this is at night, of course, and only a small amount of light should enter the door. If the hawk is frightened, close the door immediately; but otherwise you may walk about within the hawk-house for about an hour. Continue this stage for about four or five evenings and then slowly introduce the birds to the outdoors.

When first taking the bird outside, do not allow it to become frightened. During a new moon, or on a cloudy night, carry the bird out through the door and then back inside, repeating this many times until the hawk becomes quite accustomed to being carried through doorways. Continue this for about four or five nights and on the fifth night go out and stand under the eaves, at the same time offering the hawk food. If at any time during this stage the hawk becomes frightened, return to the security of the dark hawk-house. At this time the bird is weak so the diet may be generous; an entire pigeon per day is not too much. During the first night outdoors remain under the eaves about thirty minutes, gradually increasing this period to about one hour by the third or fourth night. All the time, stay close to dark places so that the hawk will sit quietly on the fist; and when moving to new places, call "ho, ho" and give the bird a little food to keep its attention. Always avoid lighted places and, when returning each night, offer the hawk water.

Introduction to light takes place at night, about the sixth night after first taking the bird from the hawk-house. At a distance of about forty meters from a light, walk slowly toward it to about four meters and then return to the darkness. Repeat this many times, each time feeding the bird small tidbits when near the light but not in the darkness. When turning away from the light, always be careful to turn to the right; thus one's back does not come between the light and the hawk. When the new hawk feeds quietly beneath the light, introduce it to people and automobiles, always letting the bird face the new object and each time giving a small piece of food. If the bird will tolerate novelties, walk past people, cars, and other new objects, noting the amount of attention she gives to these things.

After five or six days of walking with the partly-manned hawk among people and new objects, gradually reduce its diet and offer meat only when it seems to become nervous. Every night, carry the bird some four or five hours and now try to stay near brightly lighted places. If this stage was begun during a new moon, successive nights are naturally brighter. The bird can now be taken to crowded places; but, when approaching people, always move to the left so that the hawk is not upset by someone walking behind her. Similarly, if someone overtakes you, move to the left and turn your body to the right so that she can observe the passer-by, at the same time offering a tidbit of meat to distract her from a potential disturbance. By now, the bird's strength is returning, her eyes are brighter and fuller, and she holds her wings higher.

A bird that has been manned in this way is completely relaxed on the falconer's fist and feeds there eagerly every day. In fact, the fist and the food box are the only sources of food she knows. As a result, she will very quickly learn to come to the fist. It is best to begin these lessons in the hawk-house with the light to the right and the rear of the falconer. Stand in the shadows with your face rather in the dark and with your left hand hold out the prepared pigeon. Hold it just far enough from the bird so that she needs to lean forward to eat, and call "ho, ho" as she feeds. After she has taken a few bites, gradually move away; and, when she can no longer reach the pigeon, she will jump to your fist to finish the meal. A similar performance should be arranged so that the hawk will learn to come when the food box is tapped. The food box is filled with small pieces of pigeon meat; and, as it is held out to the bird, tap the bottom with your finger. This can be done outdoors, for the experience will not be entirely new. It should be done in the absence of onlookers and at dawn, so that the light gradually increases.

Great care should be taken in the first daylight experiences. The half-manned pupil will be nervous and very easily alarmed when she first taken about in the sunlight, so this phase of her education does not obviate the need for carrying in the evening and early morning. The first exercises are designed to teach the hawk to come from trees or the ground to the falconer's fist or food box. The food box, or a pigeon is to become a magnet to draw the occasionally defeated bird from her perch; and she will so realize that the outstretched hand of her teacher is a sign of friendship. Daylight training does not commence until the hawk sits calmly on the fist in full sunlight.

In terms of Japanese falconers, calling to the fist is called watari, or crossing. In the early stages of watari, the bird is kept on the leash (ôo) and later she will be graduated to a light silk creance (okinawa). With the sharp-set bird on your fist, go to an open area and throw a small piece of meat on the lawn, and when she has flown to it and eaten it, call her back to your fist, using the food box. From her indoor lessons, the "clack, clack" of the cover hitting the food box will be recalled as a signal for food, and she will progress rapidly. Next place a bite of meat on a horizontal branch some five feet away at the level of the falconer's shoulder and call her back to the food box or a freshly killed pigeon. After this secure her to a creance some fourteen feet long, and call her with an egőshi or a pigeon.

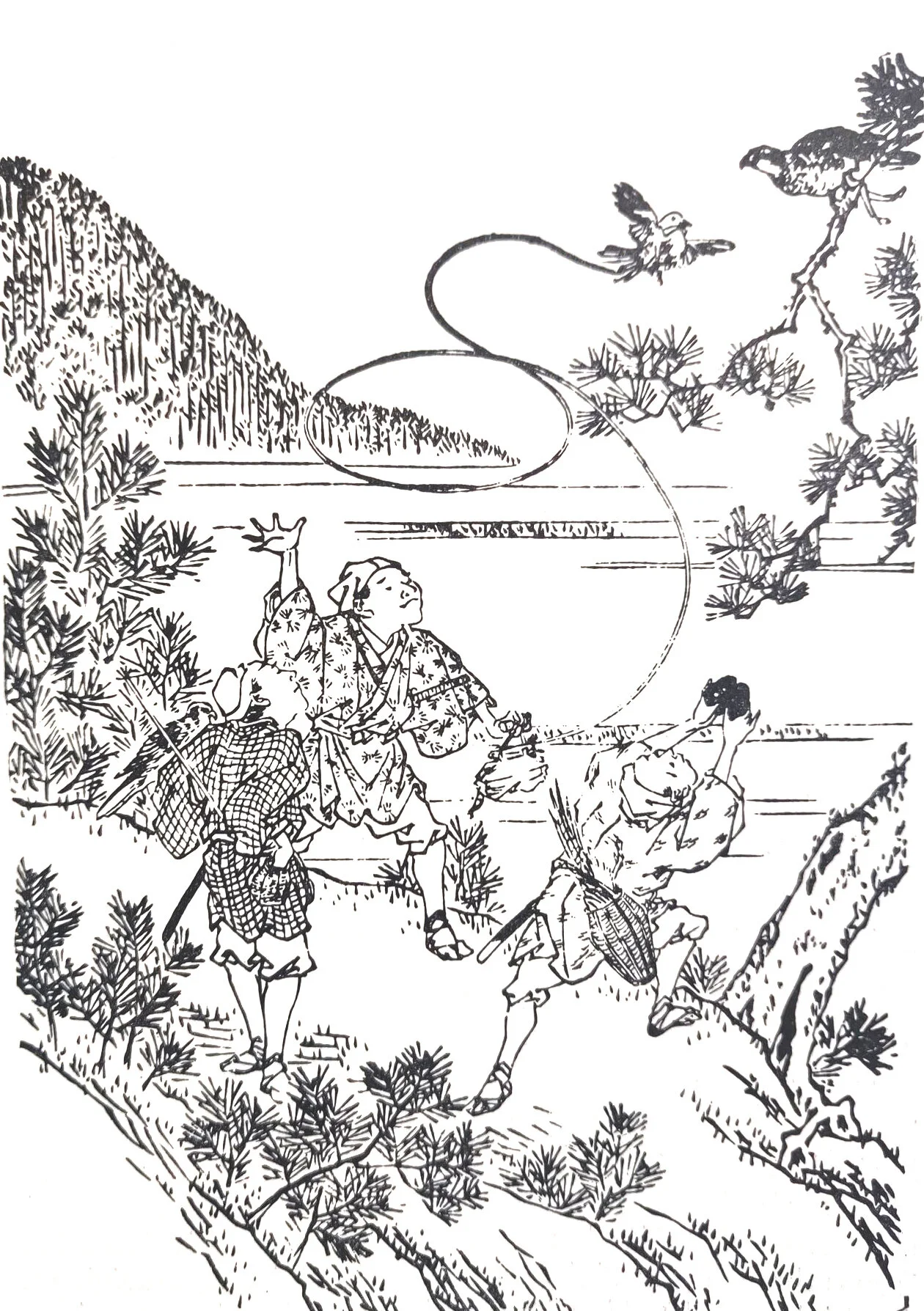

When this level of her education has been reached, let the hawk fly about 30 feet to a dead pigeon and take a full crop. Repeat these flights every day for several days. At this stage she is flying on a creance, but if she seems intent on both her prey and the food box, she may be flown free. When the hawk is loose, let her take a few live pigeons in the air. The goshawk can easily take these birds if the falconer pulls out three or four primaries from each wing. In order to give her an abundance of experience she is flown at live pigeons three times every day; the pigeon is held by three feet of creance and released by an assistant when the hawk is five or six feet away. Reward the hawk by cutting out the pigeon's heart, and then pick her up on the fist, using the food box. This part of her training will be completed some sixty or seventy days after the hawk is taken from the trap.

During the training, the hawk's breast muscles and general body condition will have built up, but the falconer must use care to make certain that his bird is strong and eager. Before introducing her to wild quarry, fly the hawk at several more bagged pigeons. For these advanced exercises a helper takes a pigeon about fifty or sixty feet away from the falconer and swings the bird about his head. Being hungry and accustomed to being flown at bagged birds, the gos will take off at once toward the fluttering pigeon; and when she is about twenty feet away, the pigeon is released by the assistant and will almost surely be captured in the air. When the hawk flies to the bagged pigeons without hesitation, she is ready to pursue wild game.

Let her first conquests be easy targets: small herons, egrets, or ducks are appropriate. Herons can often be approached when they are perched in trees. As the falconer nears the point at which the proposed quarry will fly, he must observe both the hawk and the heron. If successful, the gos is given the heart, taken up, and fed from the food box.

In these instructions there is no mention of flying to bagged ducks, which are the most common quarry of hawks of the Royal Household. Entering goshawks to bagged quarry may actually be unnecessary. In the first place, at duck ponds, the birds can be sprung virtually at the feet of the hawk; and secondly, the trained passage hawk had almost certainly been feeding on ducks until the day she was caught and she needs no reintroduction to this game. The passage from Arai (1658), quoted later in this chapter, indicates that an elaborate schedule of entering was part of the classic routine when larger quarry were sought.

Mr. Shigehiko Niwa of Ibaraki Prefecture follows a somewhat different routine, and stated that it resembled the procedure of the Tokugawa Period. Mr. Niwa advised not feeding the gos until it willingly fed on the fist. The new bird is left in the dark hawk-house for three days. On the fourth night the falconer goes to the hawk-house in the dark and feels along the perch until the hawk's feet are touched, all the while speaking softly or singing. Then he takes up the bird from her perch in the dark and carries her for several hours in the hawk-house or outside in the darkness. Each time the hawk bates, it is carefully replaced on the fist, and the conscientious falconer will put the bird back on the screen perch and pick her up again repeatedly until she is accustomed to this procedure. After two or three days the hawk will sit quietly on the left fist; at this time offer a live sparrow in the right hand. This process should be repeated each night until the hawk bates toward the sparrow. The first night the hawk tries to take the sparrow, the food is withheld, but water is offered in a small dish. The next evening allow the gos to take its first meal in captivity. If the hawk will not eat in the dark, open the door slightly so she can see the sparrow but not the falconer. If she eats, open the door more, always being ready to close it if the hawk is alarmed.

After this first meal, take up the bird early in the morning, before dawn, and carry it until the first flush of sunrise; at this point in her training, always offer the hawk a pigeon's wing as a tiring, and if she seems nervous and starts bating, return her to the darkened hawk-house. Bating is exhausting for a hawk and initial progress is necessarily slow. If the bird bates too much, return to the dark and allow her a rest. Should she continue to work on the pigeon's wing, however, carry her until the early morning light. Thereafter, the hawk should be carried about one hour in the morning and one hour in the afternoon or evening. Upon the return from the afternoon walk several sparrows (from five to seven) are given as the daily meal and the hawk is set down for the night. Condition is judged by feeling the breast muscles with the thumb and index finger, and if she loses weight, increase the diet. Carrying the hawk twice a day in this manner should continue throughout both the training period and the hunting season. If the hawk sits idle for even a single day, she will revert to some of her early wildness. When the hawk is genuinely manned, it is entered to a bagged pigeon. No attempt is made to conceal the pigeon. The quarry is tied to a string and released in front of the hawk, which is perched in a tree. As the pigeon is produced, the falconer shouts "ho, ho" and taps on the food box (egóshi), the hawk being allowed to take the pigeon in the air. The first time, the hawk is about four to six meters from the pigeon. At the beginning, both the hawk and the pigeon are on a creance. When the hawk is holding his quarry, the falconer carefully makes in and straightens forward the hawk's middle toe, whereupon the hawk will release its grip. Then the falconer taps the food box and gives the hawk a little meat. Bagged pigeons are used this way several times, and the hawk either doesn't realize that the bait is captive or doesn't care, because it is still keen for wild quarry. Later, use a pigeon in which the eyes are sealed; such a bird will fly upward and the gos will be taught to fly up from the fist.

The gos is always trained to come to the fist. The falconer places the bird in a low tree, steps back a few paces, and taps on the food box. When the bird comes to the fist, it is fed from the box.

This all requires about forty-five days from the date of capture until wild game is first taken. If a bird delays a long time before eating, it will still be ready to hunt in forty-five days. Indeed, if the hawk is slow to eat, it is likely to become a better hunter. The delay before the initial meal may be up to twenty days.

When Japanese hawking was at is glorious height, falconers successfully trained their birds to catch larger quarry than is commonly taken today. The exact key to their success may never be uncovered, but old accounts suggest the general technique. The Arai family wrote sixty-five short volumes which embody their methods and philosophy (the Arai-ryu) and one short account may be appropriately quoted here. This is entitled Kodaka Sagi Shikake and described their "secret method" for taking geese with small hawks. (The title refers to egrets, which are not mentioned in the text.) The authors are Arai Tazaemon and Arai Kyuzaburo and this volume was written in 1658. The following translation was made by Mr. Tasaburo Hada of Kyoto; the original is in rather ancient writing and, as an expression of erudition, the author sometimes made the meanings obscure.

"The ability of a hawk to capture large game depends upon the falconer. He must learn the nature of each individual bird and proceed to develop its particular abilities. This is the same as training a child, for each person is different and parents must study their children in order to rear them properly. This may seem foolish but hawks are sensitive creatures, quick to appreciate the actions of the falconer, and you must study the hawk's nature so that she may capture the most formidable quarry.

"If one day the hawk captures a small bird, the next day a larger one must be sought. It is important not to allow the bird to become discouraged. Yesterday the hawk could catch lark and quail but today it is going to catch bigger game. First you must control your aspirations and if the hawk wants to bind to the lure, let her take it. Secondly, place the lure so that it can be easily taken; maybe the hawk will be discouraged if she cannot take it. When she is on the lure, pick her up with it so that she may see what a large thing she has caught and let her take pride in this accomplishment. When the little hawk is discouraged and fails to catch the lure, place it so that she can take it easily, and then give her a generous reward. If the hawk continues to fear the large lure offer a smaller one and so build up her confidence. Teach her to recognize the shape, size, and color of the bogus quarry.

"When she is eager to take the lure, throw it out about three meters on the ground; and when she is genuinely keen on flying to it, give her a small piece of meat. When this is repeated many times day after day, increase the size of the lure and reward her when she flies well. By daily lessons she will improve. Then, give the hawk a live but very thin and weak goose or kite; and if she can attack this quarry as she did the lure on the ground, let her fly at a bird with partly sealed eyes and with the legs tied together. This is held under your sleeve. Release this goose or kite and let the little hawk catch it. Repeat this procedure with other kinds so that the hawk will learn about other sizes and colors of birds. She must be able to catch the sealed quarry instantly.

After this, show the little hawk a very strong wild goose, unsealed and unfettered, and the hawk may be frightened. Then, if she is afraid, repeat the latter exercises until she believes that she can catch big game. Eventually she will become sufficiently confident to take the large birds in the wild."

Goshawks in the days of the Arai family took geese and occasionally swans and cranes, testifying to the effectiveness of this method of training. For both eyass and wild caught hawk-eagles, the training is essentially the same, differing only in degree. For an intermewed hawk-eagle, training begins in October or November; and for a freshly-trapped hawk-eagle, the education can commence as soon as the bird is completely manned. The hawk is left to itself in the hawk-house during the molt and it will be in high condition and rather wild by the end of the summer. When the bird is taken from the hawk-house after its molt is completed, it is treated much the same as is a wild individual.

The bird is removed from the hawk-house in the autumn and placed in its small, dark box. Until the snow is deep the dark box may be kept outside, but in the winter it is more convenient to keep it in a shed where the bird can easily be attended. Every night the hawk-eagle is taken on the fist while the falconer sits quietly by the fire, this treatment continuing until the bird sits calmly and without fear. If the bird is a recently trapped adult, it should be taught to drink from a container. When the bird sits quietly at night, take a bowl of water and in it place a piece of meat. When the bird takes the meat, it will at the same time drink the water, and quiekly it will learn to drink from the bowl. The water should be clean and tepid and the falconer should always taste it first to be certain that it is not salty or foul.

For approximately twenty days the hawk-eagle is kept without a meal and gradually it becomes quite weak. At this point, and throughout this first period, the falconer must be very sensitive to the fresh haggard's condition, for not all individuals will be in the same state of health. Some birds may be rather low when first taken, and consequently must be fed more promptly. Each evening at the first stage the bird is held on the gloved fist and stroked gently and tenderly. Its first meal is of tender meat, soaked in water during the day, and offered to the hawk at night. If given fresh bloody meat every day at this stage, the hawk will revert to its wildness, so it is fed washed meat about once every three days. The manning requires about one month.

Mr. Asaji Kutsuzawa provided the following feeding schedule of a hawk-eagle drawn from the mews after the molt. The bird in question was a five-year-old eyass male and had been kept until the latter part of September on a rather rich diet customarily given to molting hawks. On the morning of September twentieth, the bird ate a fist-full (i.e. five or six ounces) of cat meat. In the morning of the twenty-third, it was given a chicken head; and in the afternoon of the twenty-sixth, it ate two chicken heads. On the morning of the twenty-eighth, it again ate a fist-full of cat meat. On the morning of October third, the bird was given the heart, liver, and lungs of a three-month-old rabbit. By October fourth, the bird's voice had changed considerably, indicating low condition. On the afternoon of the next day, he ate half of a three-foot snake. On the morning of the sixth, he ate half of a three-month-old rabbit. This was the most substantial meal since reduction began: and no more food was given until the morning of the eleventh, when he ate a fist-full of sheep lung. The next evening the hawk was provided with jesses and training began.

The period of preparation lasted twenty-three days in this instance, but it was not a fast of total abstinence. The food which Mr. Kutsuzawa gave this tiercel was low in nutrition and high in water. Until October twelfth, the bird was kept in a rather open hawk-house, and the day time temperatures were sixty to seventy degrees Fahrenheit, and a night ice formed over shallow puddles. After jesses were attached to the bird's legs, he was kept in the dark box during the day and was carried in the evening.

For hawk-eagles, carrying in the daytime (nose) is of great value, but amateur falconers are usually too busy to spend much time with their birds during the day. The dark box keeps the bird quiet in the daytime and readily available at night.

The falconer's fist is the next center of attention and a most important part, for in the field the hawk will be required to come to the falconer from trees. At all times he carries a lure, or a food box (egóshi), in which is kept a small amount of fresh meat. When the hawk learns the significance of the egóshi, she should come to it whenever she sees it. At first place the hawk-eagle on a perch about six feet away, slightly above the level of the falconer's head, and show a piece of meat from the egôshi. When the bird comes to the fist and finishes eating, repeat the exercise, increasing the distance each time. When it will come from 30 meters, it should be taught to dive at the quarry. If an eyass, the bird may be completely free from the start; but a creance is used for wild-caught birds during the early stages of training.

The first introduction to quarry is done through a stuffed hare skin, a rough imitation of the hawk's intended prey. The hawk should be placed on a perch some sixty feet away. The falconer produces the hare skin, dragging it along the ground in clear view of the waiting bird. When the hawk flies to the skin, she should be rewarded with a piece of meat from the food box; this is done several times each day, each time from a greater distance. When the bird dives at the skin with genuine spirit and gusto, the lure may be replaced by a live hare. When the hawk has experienced a tussle with living quarry, it is taken afield. This will occur in December, when the leaves have fallen and when the ground is covered with fresh, clean snow; at this time the visibility is excellent and the cold air sharpens the hawk's appetite. The transition from bagged quarry to wild game will not seem strange. For the bird's first attempts at wild hares, try to hunt in an area where they may be easily found. This will provide the encouragement needed to convince her that this new style of hunting is worth the waiting and the folderol involved in a hawking excursion. The hawk-eagle must be so relaxed in the presence of strangers that she will not become alarmed at the effort of assistants to put out hares for her to pursue.

There is, unfortunately, very little information on the handling of the sparrowhawks, but the haitaka has had a place in Japanese hawking for many centuries. In the past, they were netted by falconers, and today professional hunters catch them incidental to the capture of small song birds for the home pet trade.

First, the new hawk's talons and beak are coped, and any soiled or mussed feathers are washed with warm water. Carrying is begun at once but, in the initial period of manning, it is confined to the dark hours; bright light is avoided. This is called yozue (lit., night-carrying). These little hawks were manned by carrying through the fields and woods. Sparrowhawks were trained by rural persons (as goshawks were restricted to the nobility), and doubtless a hawk-house was not part of the establishment of an humble farmer-falconer. Thus, they carried their birds outdoors from the start. As the hawk learns to perch with poise on the fist, it is carried in the early hours before sunrise and, gradually, later in the day.

The haitaka is then introduced to bagged birds. She is allowed to bind to a tethered sparrow from which some wing feathers have been removed. If she takes the sparrow nicely, she may eat some of it. These small hawks are very difficult to feed, for if they are either a trifle too high or too low in condition, they do not hunt well. In the haitaka, condition is best judged by the violence of the bating and the position of the head feathers. When keen, the little hawk is given a sealed bird to catch in order to teach her to fly high. When she instinctively flies up from the fist, she is ready to go afield for hunting.

The general procedure for manning peregrines is essentially that set forth for a gos, but the field training of long-winged hawks is quite different. When the education of a falcon has reached the point at which she is entered to a bagged pigeon, she is taken out in an open area, quite free from trees and cover. For the first flight, place the falcon on the fist of an assistant and, retreating some twenty or thirty feet away, swing a live pigeon about your head. She will take it from your fist and carry it to the ground. Let her eat the head of the pigeon, and then hood her; this is done at about ten in the morning and she is then carried until one in the afternon. The lesson is repeated every day for about a week. During the first three or four days let her take the pigeon on the ground, but later throw the quarry into the sky and increase the distance, Also, as the pigeon is released, blow a whistle and swing the zai in the direction in which the pigeon is flying. The whistle helps to alert a hawk when overhead; and by a sweep of the zai in the direction of the game, the falcon will understand that this device is to some degree a pointer and she will learn to obey the suggestion of its movements.

In early times falcons were used to capture geese and pheasants, and at these quarry they were flown out of the hood. In such cases, the pursuit was very much like that of a goshawk and it requires no special explanation.

Also, falcons were taught to wait on as they do elsewhere. Although the result is the same, training the hawk to wait on is somewhat unlike the method of European falconers. It is termed agetaka meaning mounting or rising hawk (ageru, to raise or send up). The falconer and two assistants go to a large field and make a triangle of some six meters to a side. Each of the three has a whistle and a live pigeon. As the falconer unhoods and releases the falcon, one helper blows his whistle and swings his pigeon in the air. As the hawk flies to the pigeon thus shown, that pigeon is hidden and the other helper blows a whistle and produces a fluttering pigeon. The three men repeat this so that the hawk flies about them in a large circle. Gradually the hawk mounts and, when the falconer detects a slight tendency for her to wander, he rewards her by releasing a pigeon. From her height, the hawk has a great advantage and she will soon learn to appreciate it. In a sudden stoop, the bagged pigeon is taken.

Even at a great height, there is a bond between the falcon and her helper below, whom she watches in his effort to produce quarry. On the ground, the falconer and his dog endeavor to put up a pheasant, and if the pair can force the reluctant quarry into the air, the hawk partly folds her wings and makes her near-vertical dive. If the falcon's height is sufficient, she can strike the pheasant a crippling, if not killing, blow and the job is finished on the ground. This performance is familiar to occidental falconers and one naturally wonders if this style of hawking was not introduced into Japan by the Dutch. Japan is, for the most part, not good country for long-wings; and this suggestion is supported by the scarcity of comments on peregrines in the early hawking literature of Japan. On the other hand the zai, associated with hawking with falcons, is unknown to European falconers, and may have come from China. (The falcon can be directed by pointing the zai, but the method of instruction is not entirely clear to us today.) At any rate, long-wings have not had a prominent place in the sporting history of Japan, and the scanty information concerning these birds differs little from that found in European treatises.