Housing and Equipment

Most Japanese hawking equipment is rather distinctive, the character of certain items indicating special uses to which they are put and suggesting ways in which hawking of this small region has developed a quality of its own. Western falconers will note the unimportance or absence of such familiar items as the hood, lure, and bow perch. Some articles, the jesses and leash, for example, appear in greatly altered forms. There are some completely different pieces of hawking gear: the food box, for example, seems never to have been used by falconers in Europe. Because of our relative ignorance of falconry in China, and especially in Korea, which was the direct source of Japanese hawking, it is difficult to say which items are common to falconers of the Far East and which are indigenous to Japan. It is well known that the custom of belling goshawks on the tail is practiced throughout the East. The habit of carrying the hawk on the left fist seems to have developed within Japan, for in China and Korea hawks are always carried on the right fist.

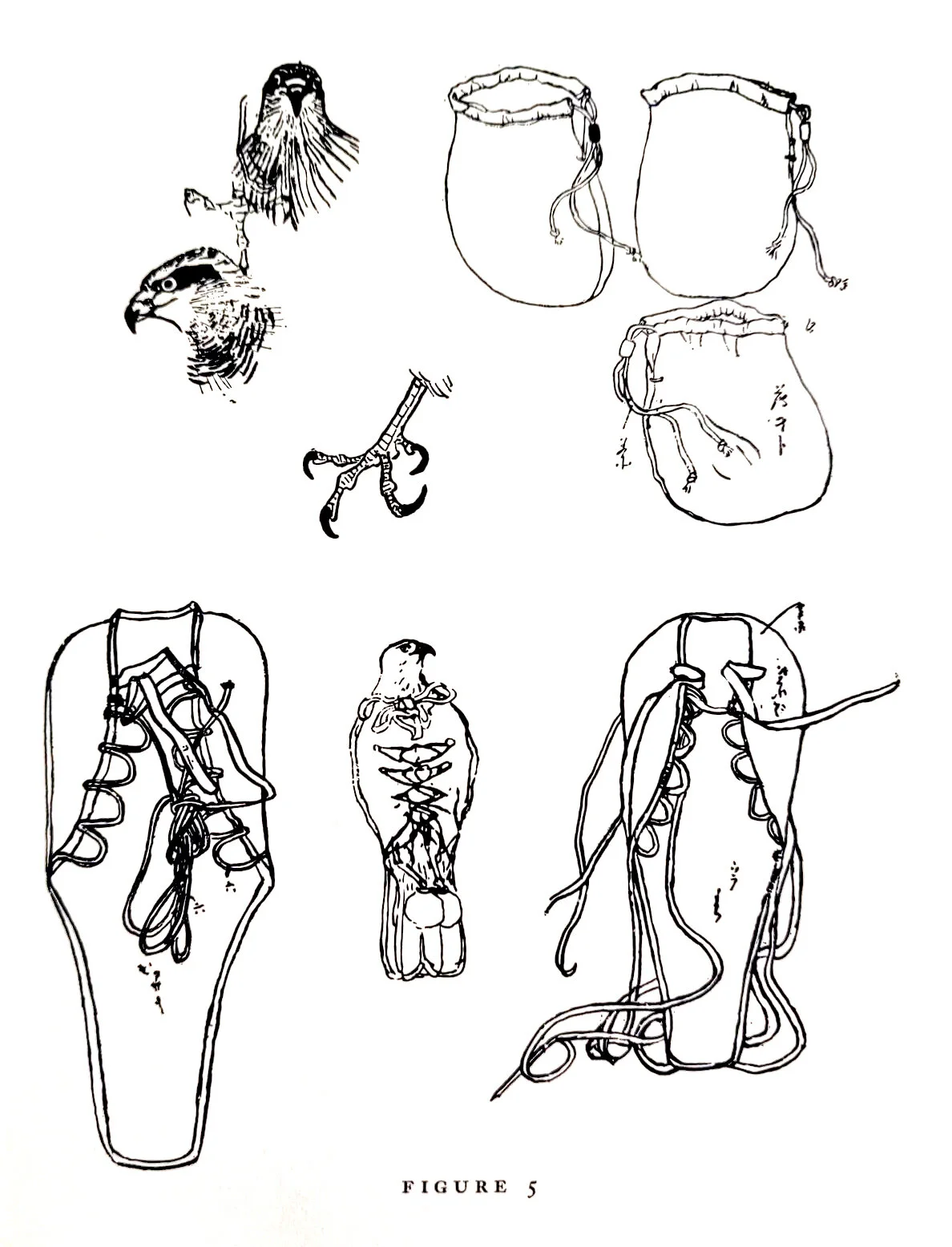

The hawk bell (suzu) is not very different from the hawk bells used in other countries. It is usually made of brass and constricted in the middle, the lower part being the larger. At the top are two small loops. The bell must be held with care to insure its ringing properly and to prevent damage to the deck feathers. To accomplish this, it is supported by a small plate (suzuita) which is usually carved from the shell of a sea tortoise or a flat bone of a fish, traditionally a carp. A leather strap is tied to each of the deck feathers above the vane and then each strap is run through one of the holes in the tortoise shell or bone plate on top of which the bell is tied. Thus, the suzuita lies between the deck feathers and the bell, preventing the bell from falling down between these supporting feathers and fraying them. The suzuita also provides a hard surface which may amplify the sound of the bell. The bell is secured by an overhand knot in the two leather straps. This simplifies removal of the bell upon return from a hunting trip. In the past, falconers believed the bell would keep the hawk awake at night. Early drawings show that variously colored tassels and feathers were fastened beneath the suzuita. These colored feathers made a hawk conspicuous so that she might be located in the field even when the bell was silent. The upper tail covert of a peacock was sometimes so employed , but generally a tuft of short feathers or colored wool was considered sufficient. One of the scrolls (makimono) of Kawanabe contains a great many types and colors of feathers on the suzuita and different sorts may have special meanings which are now lost. In ancient times, Korean falconers attached the bell to a feather of a swan and the swan's feather was in turn tied to the train of the hawk. Japanese falconers, probably quite correctly, considered this to be an impediment. Hawk-eagles are not belled. Eyasses are rather vociferous and the size of the bird obviates the need for bells.

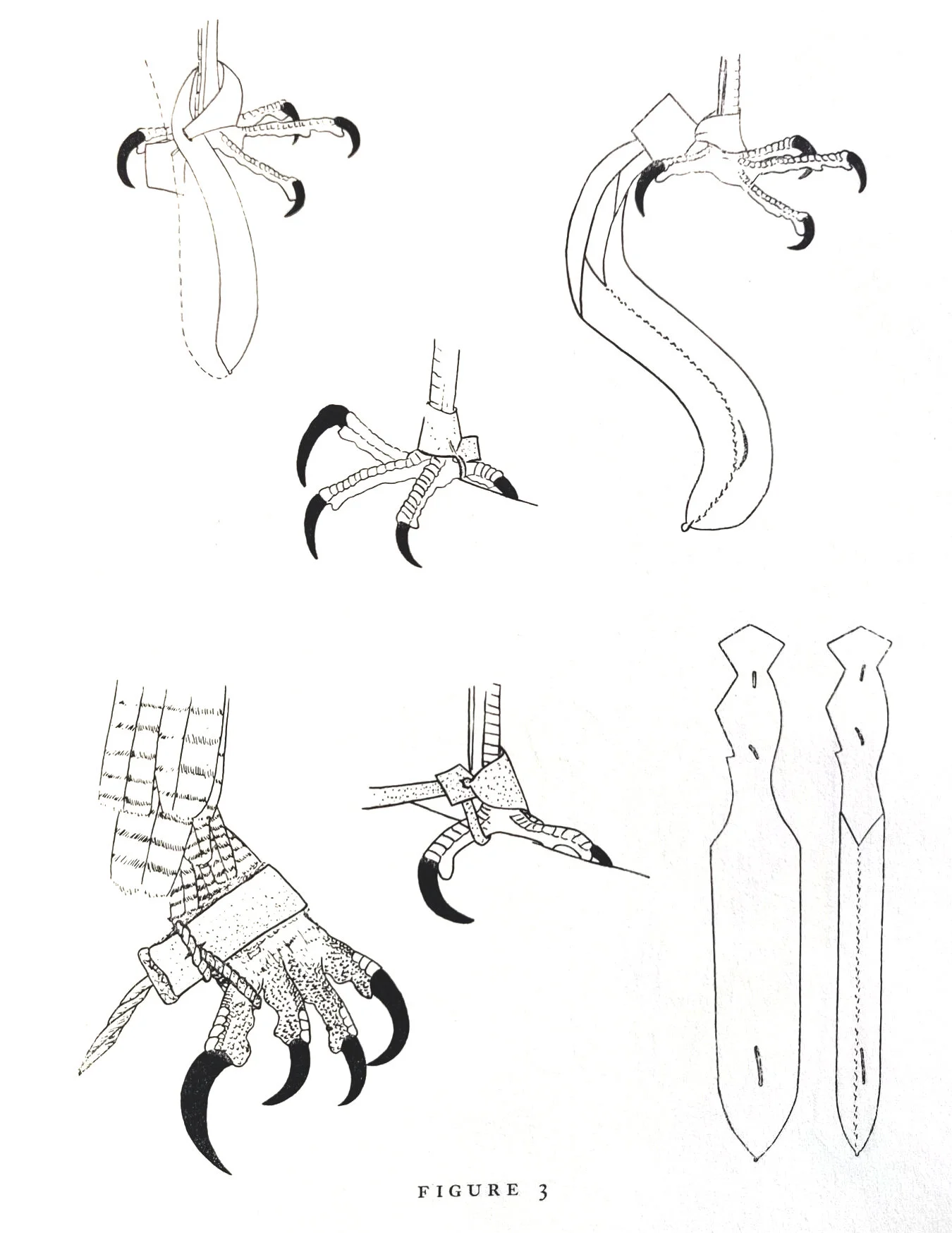

The glove, like that used by occidental falconers, is for the left hand. Ordinarily it is made of soft deerskin and at the lower edge is a leather strap by which the coiled creance (okinawa) is tied. This is about fifteen inches long and is wrapped about the creance.

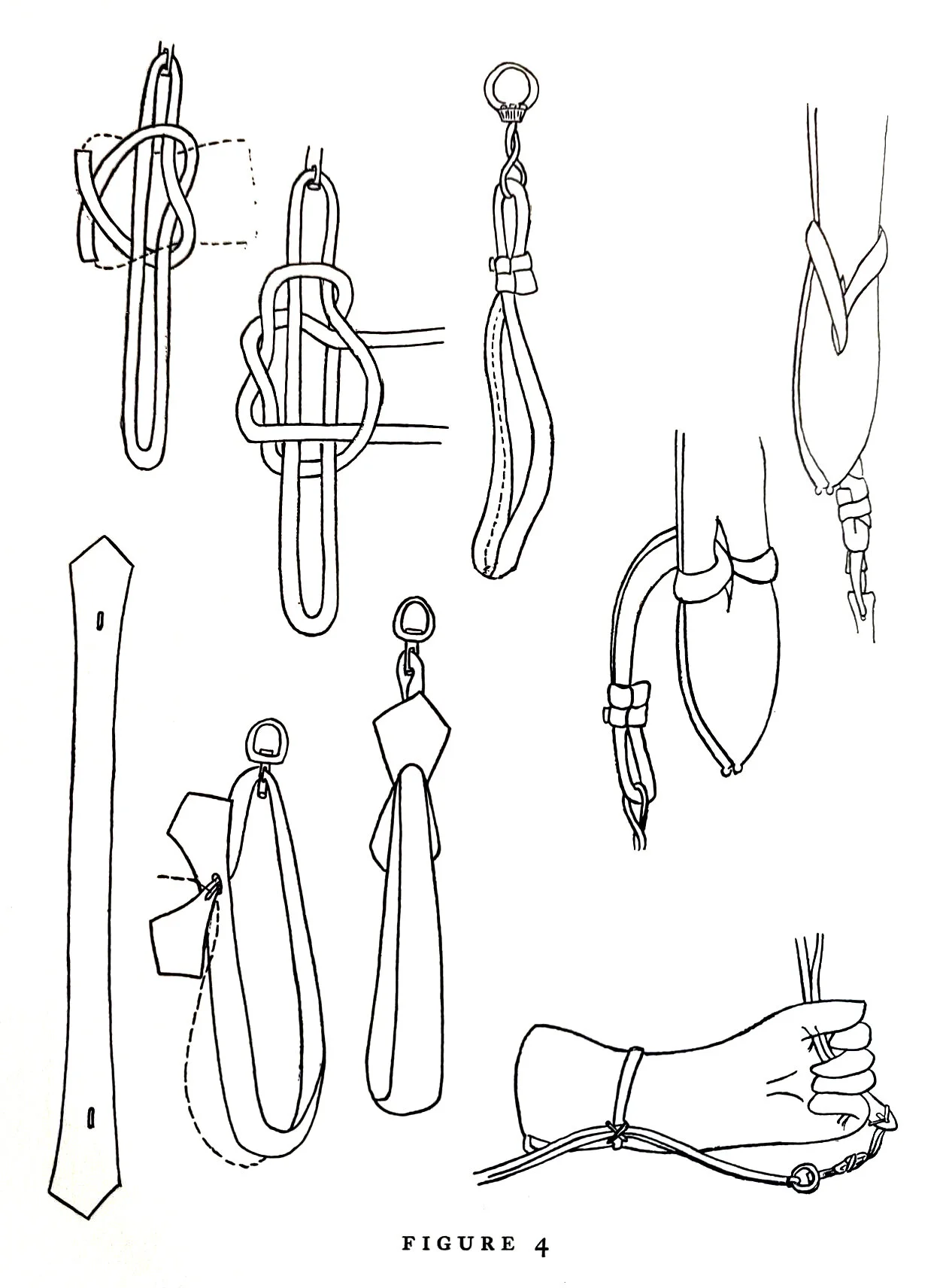

Jesses (ashikarwa) are fastened to a newly-trapped hawk or to an eyass when training begins. The nature of the jess depends upon the kind of hawk, those for goshawks and hawk-eagles being rather different. For both birds, jesses are of soft but strong leather and placed on both legs. For goshawks, the jess seems to have changed little if at all over the many centuries of hawking in Japan. The deerskin jess is sewed so that the part from the leg to the leash is double. This jess is very soft and unlikely to bruise the bird's legs. It must be remembered that Japanese falconers do not weather their hawks unattended, but rather on the falconer's fist. Thus it is unnecessary to make the jesses heavy or extremely strong. At the slightest sign of wear they are replaced with a fresh pair. The jess is fastened in a manner slightly different from that used by occidental falconers. For a hawk-eagle, jesses are about ten or eleven inches long and half an inch wide. Because the legs of a hawk-eagle are feathered to the base of the toes, the jesses must be kept from sliding up and down and so fraying the tarsal feathers. This is done by placing a small hemp loop beneath the hind toe, connecting both ends to the jess, thus holding the jess close to the toes. Excellent jesses are made of sheepskin, the furred side being placed next to the hawk's leg. Sometimes the jess for the hawk-eagle is made in two parts: a leather (sheepskin) piece encircling the tarsus and an eight or nine inch cord which the falconer can grasp with his hand. A third type is provided with a ring instead of a cord and a leash is run through the ring on each jess. As hawk-eagles are rarely weathered on an outdoor perch, there is little wear on the jesses and cotton cord is amply strong.

The leash (ôo) is a long cord of woven fabric, variously colored. For falcons, the leash is linen, but silk is used for a goshawk, indicating the greater regard Japanese falconers have for the latter species. The method of tying the leash to the screen perch was once elaborate and varied with the season of the year, special festivals, rank of nobility in whose presence the hawk was placed, and the species of hawk. Modern falconers are more functional than fastidious with respect to such matters. The swivel is similar to that used by occidental falconers but is attached to a leather loop about five or six inches long. The loop, together with the swivel, is termed musubi and is made in various ways. In other words, the jesses are attached directly to the musubi of the leash and not to the swivel. The leash can be fastened in a temporary fashion when the bird is taken afield or it can be made more secure when it is tied to the screen perch. The difference in the two is apparent from the drawings. Newly-captured hawks are placed in a special sack called fusegimi (lit., cover cloth). It may be of fabric (usually linen), woven straw or fine bamboo. The fuseginu may be of cloth stiffened by a piece of wood sewed in the back. When the affair is laced down the front the hawk is held immobile and the falconer can cope the bird's beak and talons, and attach jesses and a bell with no danger of being hurt or of injuring the hawk. While the beak is being trimmed, the feet are placed in small deerskin bags to protect the falconer. The sketches of the heads and feet illustrate the degree to which the beak and talons are coped.

Because long-winged hawks held a position of less popularity, their gear is not well known and rarely used. For falcons, a very distinctive type of lure is employed. The falcon's lure (zai) consists of a tassel of fifty or sixty white strips of paper (or sometimes cloth) tied to a thirty-inch stick. Meat is tied among the white strips and the falcon soon learns to associate the zai with food. It is used to recall a falcon from a distance and is indeed very conspicuous when swung back and forth over the falconer's head. It is also used to direct the flight of a falcon when it is waiting on. When a shogun went hunting, he used a white zai; other falconers used a red zai.

In both ancient and modern Japan the hood has had no place of great importance, although some old illustrations show that hoods were once used. The books of the Arai family (1658) mention the use of hoods in training goshawks. As in other parts of the world, falcons in the field were kept hooded until flown, and an interesting illustration from Ehon Taka Kagami (Fig. 6) shows goshawks being flown out of the hood at geese. Present day falconers in Japan do not use hoods, perhaps because the original style was not really good enough to be advantageous. Also, falcons are seldom trained in Japan and for the more popular goshawk, a hood is unnecessary. Instead of hooding his bird, the Japanese falconer today is more likely to transport it in a tall box. This is easier if one has to travel on a crowded train to a hunting area, as is so often the case. Mr. Tsuyoshi Kuto has adopted a modified Indian hood for use with hawk-eagles, and finds that it facilitates handling these birds in the field.

For arranging the hawk's feathers and wings and for removing meat from the bird's beak falconers use a special stick called a muchi. It is usually made of wisteria because this wood is very light and easily bent. The tip is split into many fine short pieces so as to make a short stiff brush. Because, in ancient times, a hawk actually belonged to the shogun, the falconer was not allowed to touch the bird with his hands, but had to use a muchi. This device serves the more practical purpose of protecting the hawk's plumage from dirt or grease which may be on the falconer's hands and is still used by a few Japanese falconers today.

Among different pieces of hawking equipment are some articles which suggest the atmosphere of Japanese hawking. It would be quite inaccurate to say that hawks are not flown loose in Japan, but there is a tendency for some falconers to keep their birds tethered even when hunting and special types of creances have been developed for this purpose. The conventional silk creance (or okinawa) is tied to the jesses during the period the hawk is being trained. Also, when flying a gos at a duck pond, it is desirable to keep it confined to a small area so as not to frighten the waterfowl on other parts of the same pond. Here the okinawa may be tied to the jesses. In the past, when it was the practice to net ducks at a baited pond, one or two trained hawks were held to release at any teal or mallard that might escape the clap-net. This creance is attached to a leather piece which can be fastened to the jesses. The creance is wound about a small piece of bamboo and the leather end placed in the hollow center of the bamboo. The silk is so smooth that, when the leather end and bamboo core are pulled out, the okinawa offers no friction and gradually falls out by its own weight. Thus, it does not impede the hawk's flight. The coiled creance and its bamboo core are tied to the falconer's glove. A special light, but strong, creance (mizunarwa) is waxed and used to tether the hawk when it is bathing out of doors.

An extremely light creance (kiriheo) was, in times past, tied to the jesses of a sparrowhawk when it was flown among trees. In a forest, the small hawk was apt to disappear from sight. At the end of the kiriheo is tied a small feather from a swan and the white feather could be seen in poor light of the forest. The silk thread and feather offered no drag to the hawk's flight. Also, even though the sparrowhawk was free, should she refuse to come down from her high perch, the falconer could probably reach one section of the kiriheo.

The screen perch (hoko) in Japan is of several sorts, some being rather like those used in occidental hawk houses. For use in the hawk house, the screen is a rice straw mat. This is laid over a horizontal pole so as to form both a pad for the perch and a pendent screen by which a hawk may regain its position after bating. Thus, the screen is of two layers. The perch itself is traditionally made from either cedar or Paulonia, as these woods are rather soft and have a certain amount of resiliency. This elaborate affairs were used in the homes of the daimyos. Such screens were beautifully decorated silk with intricate designs and embroidered pictures.

A very low horizontal perch (jiboko) was used for untethered fledglings. Beneath this perch were spread leaves or mogusa (Artemisia moxa), an oriental plant allied to wormwood and sagebrush. The fragrance from these leaves was believed to refresh the young hawks. Possibly falconers adopted this practice after seeing fresh foliage in the nests of hawks. Also, for temporary use in the field, a simple perch was made of a pole suspended between two tripods. These perches were sometimes without screens and it is unlikely that birds were left there unattended. Devices similar to T-perches seem to have been used in the past and are still used in some localities for hawk-eagles. Bow perches, however, have never been a part of Japanese hawking equipment.

A special sort of perch was, in the past, used when flying merlins. Because these little falcons have a penchant for carrying their quarry to a high perch, the falconer would carry afield a T-perch on a vertical pole of some four meters. When propped up near the victorious little hawk, this high T-perch made an inviting site on which she could plume her prey. When she was settled on top of this long pole, the falconer gradually lowered her until an assistant could take her up. This type of T-perch is shown in a delightful drawing which includes many other items of antique hawking gear.

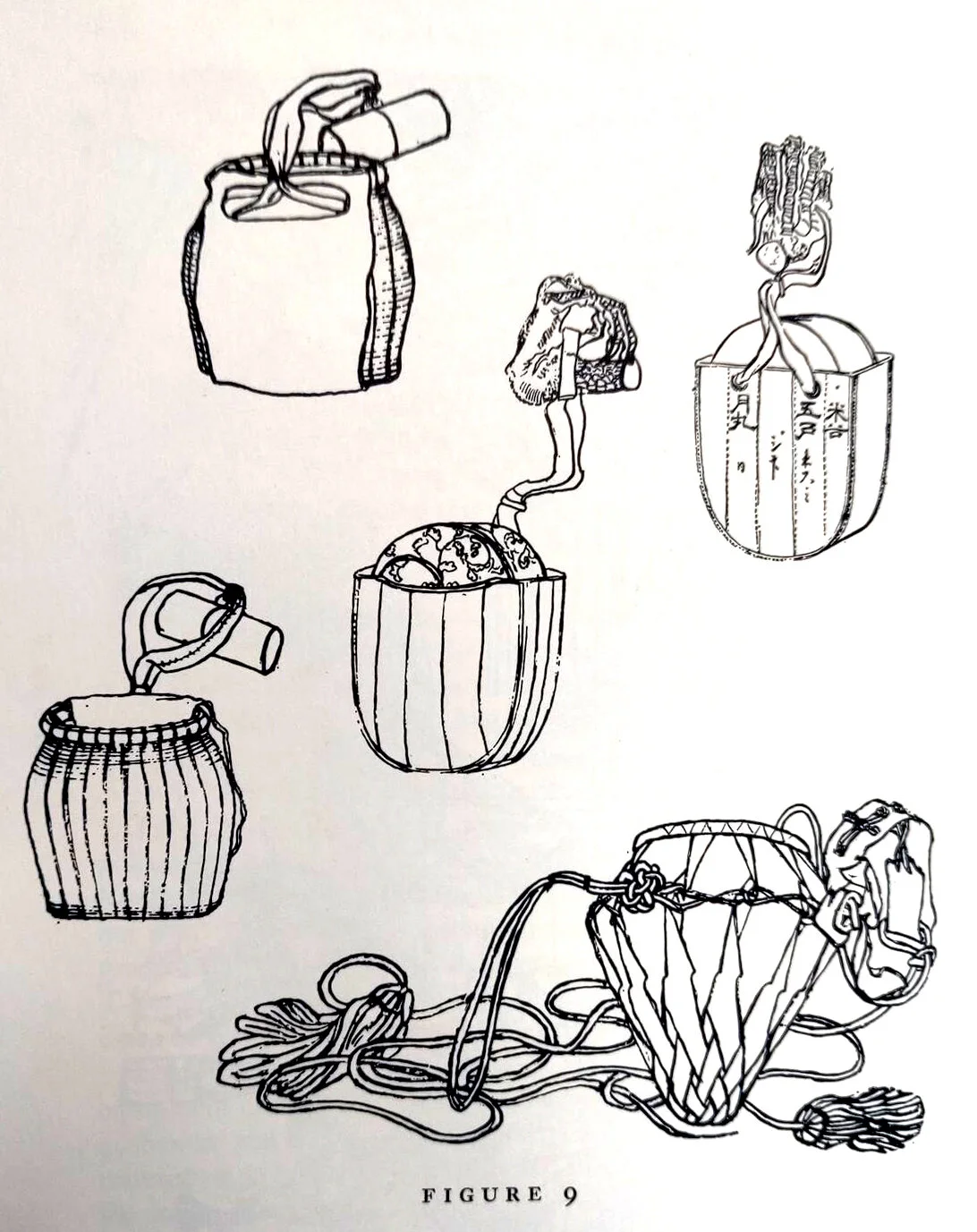

The food box or lure-box (egôshi) is a very characteristic piece of equipment used by falconers in Japan and is used in the training of both goshawks and hawk-eagles. It is a wooden box, either lacquered or unfinished. If lacquered, it is colored black on the outside and red on the inside. Commonly, from the side view, it is oval and rectangular in cross section and is held in a stiff leather or lacquered case (Fig. 9. center and upper right). The case is held by two leather straps which are tied to the foot of a crane or a short piece of wood or bamboo (netsuke) which is tucked under the falconer's belt. Most food boxes measure about 1½x3x4½ inches. Usually the lid simply fits into the top, but in some egôshi the lid slides in grooves. A sliding lid permits the falconer to terminate the bird's meal by slowly closing the lid over the food. The hawk then does not feel that the meat is being snatched away from her. By tapping the box with his knuckles or finger tips, or by hitting the lid against the box, the falconer can call his hawk and naturally she quickly learns to associate this sound with food. This characteristic sound carries well enough to be used to draw a hawk down from a distant tree. Some falconers in Japan believe that a trained hawk will never overcome its fear of the human voice. If the hawk is usually fed from the food box, she is unlikely to grab the falconer's hand. In time the food box becomes thoroughly clawed by the foot of the anxious bird and the falconer's right hand is thus spared these attacks.

A food basket (kuchiekago) is used to hold bodies of small birds and, like the food box, is tied to the falconer's belt. It is most commonly used when hunting with sparrowhawks or merlins, which are more likely to be fed entire bodies of birds. (If food is cut up in small pieces with no castings, it is always put in the egőshi. Because it is rather tight, small pieces of meat do not dry out.) An earlier type of food container used in the Heian Period (794-1392) was called takaefugo and apparently served the same purpose. Also used when flying sparrowhawks, and perhaps merlins as well, is a linen sack (ikebukuro, lit. live sack) provided with draw strings. The ikebukuro is the container for small birds which are used as live lures to call down a shy or stubborn sparrowhawk.

For training hawk-eagles, an essential piece of equipment is the light tight box (takabako, lit. hawk-box). The newly trapped or mewed hawk-eagle is kept in a box which measures about three feet seven inches high, two feet two inches wide, and four feet four inches deep. To fulfill its function, it must be comfortable and well ventilated and still dark. There is one transverse perch, as well as several holes (concealed by baffles on the inside) for fresh air. This box is essentially like that which was once used for freshly-trapped goshawks.

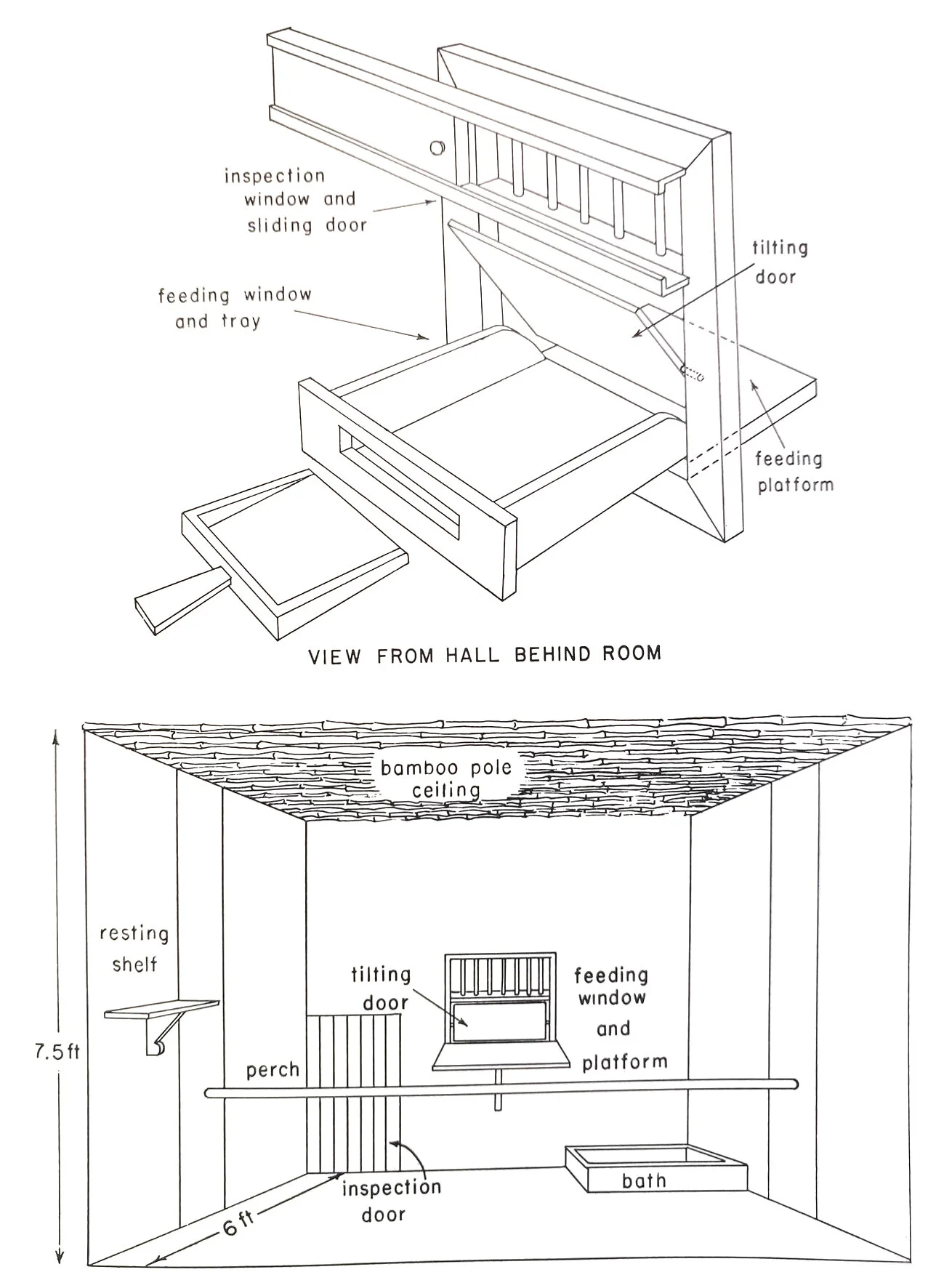

As elsewhere in the world, the hawk-house varies with the ingenuity and energy of the falconer and various styles exist in Japan. Those presently used for goshawks by the Royal Household represent the ultimate in planning and are probably rather like those used in the past in the establishments of the daimyos. The hawk-house or takagoya at the duck ponds of the Royal Household consists of five separate rooms, each of which is a unit and accommodates one bird. Each room can be darkened for a newly-captured hawk or made light and airy during the molting season. The illustrations are simplified to show the essential design of one room and measurements are in shaku (approximately one foot). In the rear is a long hallway with a separate entrance to the outside. From this hallway, there are two entrances into each room: one is a low door for access during the molting season, allowing the falconer to enter and pick up stray feathers; a second door is an entrance to provide food during the molting season and consists of an upper barred section with a sliding door for inspecting the room and a lower section with a sliding tray. At the bottom of this opening, inside the hawk room, is a platform on which the feeding hawk can stand. On the opposite side of the room is a large sliding door through which the falconer can enter to take up the bird for hunting. Across the room may be placed a single perch, provided with a screen if the hawk is tethered. The floor is concrete, but covered with a generous layer of clean sand; in one corner is a square bath. The ceiling is built of closely placed sections of bamboo, permitting the entrance of light, fresh air, and rain. The roof is partly removed during the molting season, at which time the bird is loose; during training and hunting the roof is replaced, darkening the chamber.

For hawk-eagles the building is rather different; there is no need to darken their house because of the use of the dark box during the training and hunting periods. For the large kumataka, the hawk-house is placed in a dry sunny area, well ventilated, and near running water. The building itself is about six or seven feet on each side; and the walls are made of slats or lathing about two and a half inches wide and placed vertically about two and a half inches apart. If possible, a stream is diverted so that it runs through part of the floor of the hawk-house, providing water for drinking and bathing. Two straight branches about two inches in diamețer, complete with bark, are placed horizontally in opposite corners. The floor is covered with gravel or coarse dirt and must be kept scrupulously clean. The wall construction permits excellent ventilation and the fresh water enables the bird to keep itself clean and sanitary. For a very young eyass, a special nest of warm cotton or rabbit fur should be provided. A nest is unnecessary if the bird is more than twenty days old.

Except in the case of a newly-caught hawk, Japanese falconers place their birds loose inside the takagoya. This provides the bird with a limited amount of exercise. This movement may not be especially useful in strengthening muscles, but it seems to speed digestion and stimulate the appetite. There is a minimum of damage to feathers of birds which are kept loose in hawk houses. The hawk-eagles of Mr. Kutsuzawa, Mr. Tomita, and Dr. Sano were feather perfect. Broken feathers were seen only on hawks which were constantly tied to screen perches.