History of Hawking in Japan

There is some uncertainty as to when the sport of hawking first appeared in Japan. An early Japanese chronicle, the Kojiki, recorded that hawks were used in very early days as a regular method of capturing birds. The Kojiki mentioned events that occurred as far back as 650 B.C., although the Kojiki, as a written document, dates from 712 A.D. Very early evidence of Japanese hawking exists in the form of a clay model (haniwa) of a trained hawk, which was found among other earthen images buried, as was the custom, with the leader of a noble family. The bird was belled on the tail, and, therefore, seems to represent a goshawk. The use of haniwa was established by the year 3 A.D. and continued until about the sixth century. This haniwa was found in Gumma Prefecture and dates from about the sixth Century, A.D.

Trained goshawks were brought from China to Japan in the forty-seventh year of the reign of Empress Jingu (244 A.D.). The training of hawks was apparently not maintained, and the sport may have been andoned for some hundred years. In the chronicle Fudoki is a chapter about the hill called Suzukui no Oka. During the reign of the Emperor Homuda, immediately prior to Emperor Nintoku, a hawking party was hunting on this hill and lost a hawk bell. The bird was subsequently lost, and therefore the hill was called Suzukui no Oka (the hill that ate a bell). Thus, trained hawks, with bells, were used at least one reign before Nintoku.

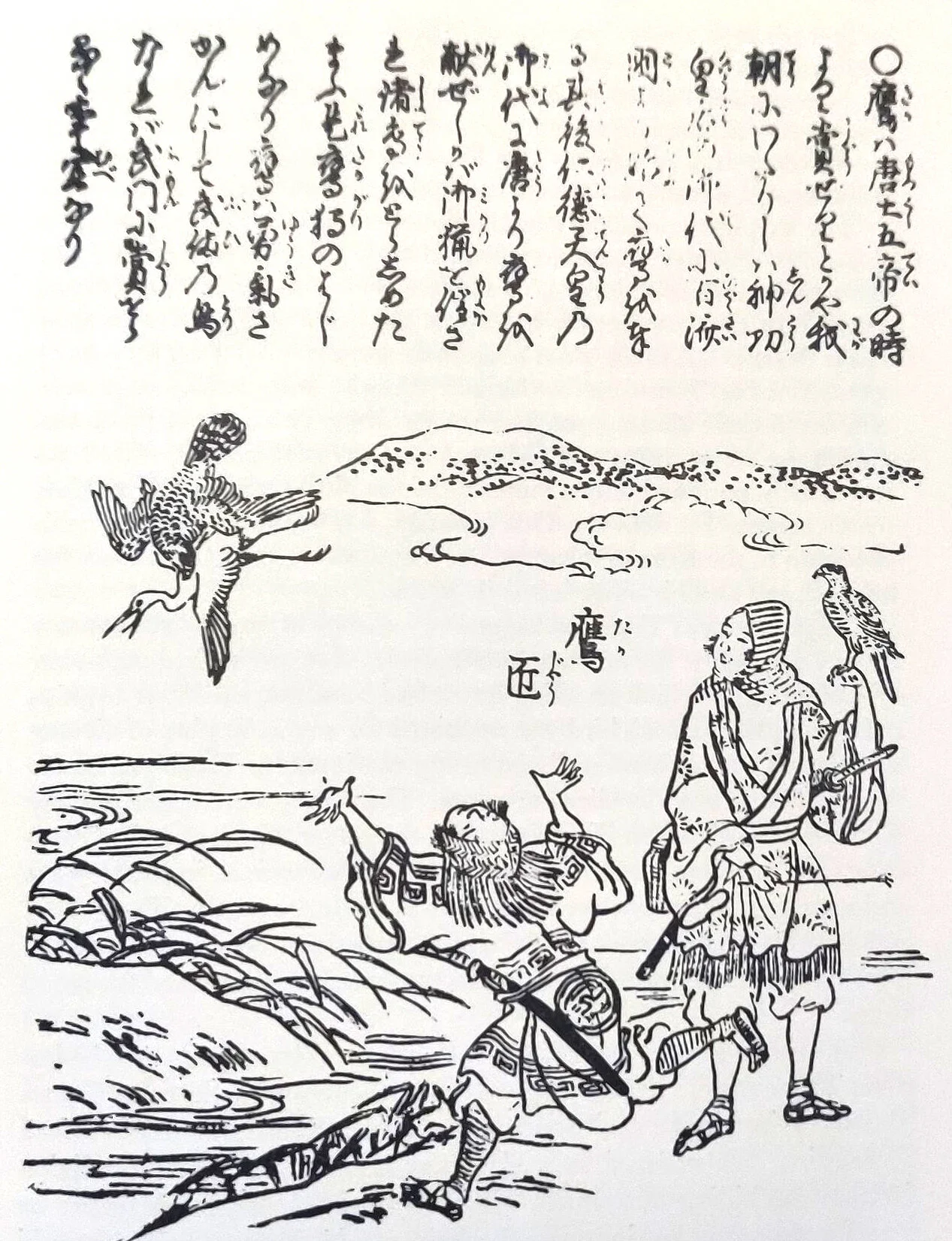

About 355 A.D., according to most sources (e.g., the chronicle Nihonshoki), during the reign of Emperor Nintoku, the actual practice was finally initiated in Japan. One Yosamimiyake Abiko caught a strange bird and presented it to Nintolku. In all the court only a Korean, Sake-no-Kimi, recognized the species. He explained that it was a hawk (almost certainly a goshawk) and used in Korea for hunting. The Emperor charged Sake-no-Kimi with training this bird. The hawk was furnished with jesses on its legs and a bell on its tail, and trained that summer. In September it was taken to the fields of Mozu (near present Osaka), where it caught many pheasants. This story is told in many old accounts.

Emperor Nintoku established a special organization, the hawk office (takakaibe or takakambe), for the care and training of hawks and placed Sake-no-Kimi in charge. This office was perpetuated and about two hundred years later, under Emperor Senka, a dogkeepers' office (inu-kaibe) was set up to train dogs to hunt with hawks. From that time both these offices were associated. In 701 A.D. the takakaibe was reorganized along military lines and given importance comparable to that of the army and navy. From the beginning, hawking belonged to the nobility, and most feudal lords had falconers on their staffs.

During a war with Korea in 1596, Toyotomi Hideyoshi met with a Korean general who offered hawks to the Japanese army in exchange for food. So great was their love for hawking, the Japanese military personnel effected a temporary cessation in the war. This episode was followed, if it did not indeed cause, a lively interest and commerce in goshawks from Korea. Tokugawa Ieyasu, after Toyotomi Hideyoshi, designated governors (daimyos) throughout Japan, including the twin islands of Tsushima, which lie between Korea and Japan. Hawks were very much in demand by the nobility and, since Korean hawks were imported to Japan through Tsushima, the governor of that province acted as a middleman in the trade. He tried to keep his compatriots provided with a steady supply of wild-trapped goshawks from Korea and in turn the Koreans sent many birds so as to maintain friendship with Japan. Most were passage hawks, which were preferred to haggards. In 1644, when a son was born to the Shogun lemitsu, a delegation of four hundred Koreans brought a congratulatory gift of many books and twenty trained hawks. The Koreans had traditionally presented hawks to the diamyo on Tsushima to celebrate the birth of a son.

The shoguns continually asked the Koreans to send goshawks to Japan for they never had enough of these highly valuable birds from the continent. The daimyo of Tsushima found himself in the difficult position of trying to supply a demand greater than he could seem to meet. Because the birds often became ill en route to Japan, they were quarantined on Tsushima for thirteen days and only healthy ones were sent on to their destinations. Korean falconers cared for these hawks during their quarantine and fed them at their own expense. The food was usually poor and only a minority of the birds arriving at Tsushima were accepted for delivery. One goshawk was worth twenty-five rolls of cotton to the Korean falconer, but his expenses, travel and food, for both himself and his birds, left little profit.

The governor of Tsushima suggested a change in procedure to ensure the good health of the arriving hawks. A new law prohibited the re-use of a building in which an ailing hawk had been housed. Prior to shipment from Korea, each bird was examined for any indication of disease; and, only if a hawk were well and strong was it sent to Tsushima. In this way, fewer goshawks died en route. The birds were cared for by Koreans who lived on Tsushima, but they soon tired of being caretakers for transient hawks, and again the birds received improper care and were sometimes not even turned over to the governor. Thus, there was usually a back order of goshawks, sometimes for as many as one hundred and twenty birds. The trade, nevertheless, continued for many years.

Following a precedent set by some earlier rulers, the Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, in 1684, stopped the traffic in goshawks from Korea. Tsunayoshi, a bit of a spoil-sport, was a devout Buddhist and prohibited all hunting. He ordered trained hawks released because his religion forbade the killing of animals. He even decreed that other names be used for the many sections called takajo-machi. As soon as Tsunayoshi died, falconry flourished. Many Buddhists had suspended hawking for a time. An identical law was enacted by the Emperor Jinki in 724 A.D., and in 765 A.D. the Empress Shotoku not only stopped hawking but halted the capture of small river fish (ayu) by trained cormorants. In 706 A.D. Emperor Kanmu restricted hunting with hawks to the nobility. Violators were severely punished. At some time in the Heian Period (from about the ninth to the fourteenth centuries) hawking was gradually resumed. Hawking parties sometimes were so large and wideranging that they damaged rice and other crops in their excursions. In some cases trained goshawks followed their quarry into temples and made kills in sight of the Buddhist priests. Hawking near temples was thereupon prohibited. During the Nara Period the Empress Gensho, in about 710 A.D., banned hunting and ordered the release of all trained hawks. In spite of these repeated prohibitions, it is obvious that enthusiasm for hawking endured, and one is inclined to wonder how effective these decrees were even in their time.

Ownership of a goshawk was restricted in early days but requirements were variable. Under the daimyos, a lord who received fewer than one hundred thousand koku of rice annually from his farmers was not allowed to maintain trained hawks. (One koku is about five bushels.) This restriction was apparently confined to goshawks and peregrines. Hawk-eagles and sparrowhawks were probably trained in mountainous regions, but the nobility chose to overlook hunting with these raptors. By ancient standards, hawk-eagles were not noble birds. Class distinctions remained to some degree and birds owned by an emperor were identified by a purple leash; other leashes were red, except that a hawk that had captured a crane was entitled to wear the honored purple.

The abundance of old illustrations of trained birds is evidence of the popularity and position hawking once enjoyed in Japan. Almost all are goshawks, and light-colored individuals, prized for their unusual appearance, were often painted. In ancient Japan, goshawks from Korea and areas to the north were the most highly regarded, and these birds tended to be rather pale in color. Only occasionally is a falcon or a hawk-eagle depicted; and some of the paintings of falcons are copies of works by Chinese artists. These paintings, frequently decorations of folding screens, consisted of carefully drawn and delicately colored paintings of trained hawks in various poses; and the excellence of these drawings indicate that the artists were well acquainted with the postures and mannerisms of trained birds. From the finished workmanship and elaborately decorated screen perches (hoko), we can assume that trained hawks were often kept inside the homes of the daimyos.

In the Heian Period a Chinese falconer, Oyo Kanemitsu, came to Japan with an ancient text on hawking. His training methods were so successful and admired that the authorities were loath to let him depart. To persuade him to remain in Japan, they selected for him the most lovely and charming young lady from a group of one thousand court beauties. This girl, Kuretake, produced a daughter, Akemihikari, who became as ardent and talented a falconer as her father. At maturity, when she married Minamo Tokurabito Masayori, her father gave her eighteen books of his secret methods and a set of thirty-six oral instructions on the care of trained hawks. The method became very popular and was known as the Masayori-ryu or Masayori method. There were, from time to time, a number of other “secret” methods, each bearing the name of a famous falconer. Actually these so-called secret methods were all rather alike.

Special areas were designated for hawking in the middle of the Heian Period, and here the emperor used to hunt. Previously, falconers donned functional attire, but gradually they wore more elegant dress. On hunting trips, the participants began to spend more time in social events, games, poetry, and dancing; and hunting areas became regular sites for relaxation of the nobility.

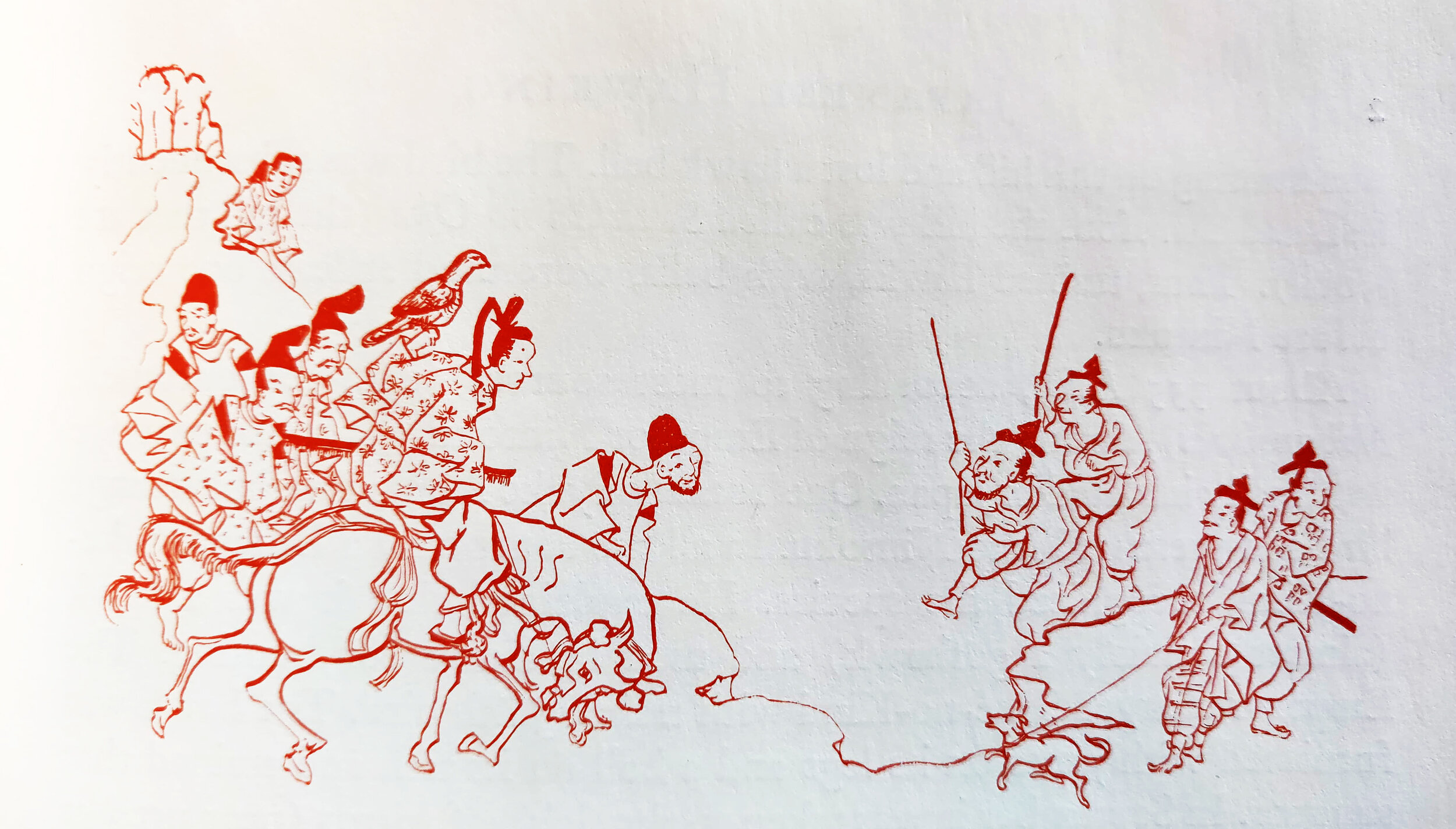

In the Muromachi Period, hawking played a role in military campaigns. Miyazaki Okinokami and his men (in 1562), hoping to catch their enemy off guard, wore the distinctive garments and gear of a hawking party over their arms and armor, and pretended to hunt near the enemy castle. When close enough, the warriors removed their camouflage, rushed in, and quickly overpowered the surprised opponents. Falconers were also sent into households of the enemy to act as spies.

Falconry alternately flourished and faded but reached its greatest popularity in the seventeenth century, under favor of the Tokugawas. Tokugawa Keiki and the Tokugawa clan in general, enthusiastic supporters of hawking, brought the art to its highest level of perfection in Japan. Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of the keenest falconers among the nobility, followed hawks until he was bedridden, at the age of seventy-five. On one eleven-day hunting trip, his hawks captured twenty-five cranes, eight swans, and many ducks. The number of hawks flown was unspecified, but thirteen were wounded in capturing the quarry listed. Tokugawa Yoshimune encouraged interest in hawking for he considered it especially appropriate for soldiers; this earned him the name of takashogun (hawk-general). Like Japanese falconers before and since, the Tokugawas prized goshawks, and granted land rights in exchange for eyass goshawks from the upper slopes of Mt. Fuji. The falconer's salary was increased if he found a nest and he received a bonus for each hawk captured. At this time many game preserves were set aside for hawking and such areas were the favorite resorts of the nobility; and these sites sometimes also served as meeting places for secret political gatherings. Hawking excursions to and from these preserves were also used to conceal a lord's inspection of his lands. At such times, the party would eat and sleep in farmers' homes, where they could observe the lives and hear the attitudes of the people. Because of its enthusiasm for hawking, the Tokugawa family gradually accumulated a group of very skilled falconers and their establishment was elaborate. A special group of persons called esashi had the job of procuring and preparing the small birds fed to trained hawks. They all lived together in a separate section of the city (esashi-machi) and in a different area dwelled the falconers (takajo). Certain sections in many cities of Japan still carry the name takajo-machi.

Sometimes certain farmers were selected to protect the game in their neighborhood. As a symbol of authority they were permitted to carry a sword and were also granted the honor of a family name. (In ancient Japan common people were little above livestock, and only those in higher social positions possessed family names.)

The Meiji Period inherited the Tokugawas' falconers, with their skill and knowledge, but the rulers lacked dedication and devotion to hawking, and the sport suffered a severe setback. In 1866 hawking ceased in the Royal Household, but interest in 1882 resulted in the establishment of a special hunting preserve (goryoba) for the emperor. One Murokoshi Sentaro was falconer to the Emperor Meiji; later Kobayashi Utaro preserved hawking in the Royal Household. In Japan as in Europe, the introduction of firearms was undoubtedly associated with the decline in falconry. A hawking establishment has been maintained, however, and one or two goshawks are still annually trapped and trained at the duck ponds of the Royal Household in Saitama Prefecture. Birds are also obtained as eyasses (sudaka) in the interior of Honshu. Most important today are the passionately dedicated falconers for whom hawking is a lifetime obsession. These isolated amateurs have trapped, trained, and flown hawks under conditions far more confining than those experienced by those in western countries.

Today hawking is under many restrictions, the most discouraging of which is a scarcity of game. It is very difficult for a falconer to find an abundance of quarry unless he lives in the mountains or in a place where birds are baited and protected. Urban falconers sometimes buy domestic pigeons and travel to the country, where they release them near trained hawks. This is admittedly a very dilute form of falconry but the best that some can have. Hawking in rural areas is conducted under more natural conditions, but the classic quarry, geese and cranes, are no longer found in any numbers, and cranes are rigidly protected by law. Sometimes hares and pheasants can be located, but the austringer needs beaters for hares and a good bird dog is considered highly desirable for taking pheasants. Coots and occasionally small herons (the later illegally) are taken by goshawks as they pass through central Honshu en route to the north from late April until June.

Despite the small number of falconers now flying birds in Japan, the sport is maintained separately by a number of austringers. In addition to the goshawks of the Royal Household, a number of other persons train goshawks or hawk-eagles. Communication is so poor among tra- ditionally publicity-shunning falconers, however, that many must be unknown to their colleagues. There have been several well-attended public demonstrations of trained peregrines and goshawks at bagged quarry. These exhibitions have been organized and conducted by Mr. Arie Niwa of Nagoya and Mr. Tsuyoshi Kuto of Uwajima. Mr. Shigehiko Niwa of Ibaraki Prefecture has prepared a film showing flights of trained goshawks. There also have been films for television and cinema of the magnificent hawk-eagles of Mr. Asaji Kutsuzawa. Dr. Masaki Sano of Wakayama has privately made a very excellent movie showing his use of several species of short-winged hawks.