Consummation

Japanese austringers took a variety of very impressive birds, including such powerful quarry as geese and cranes, which must be rarely, if ever, taken by wild hawks. Hawking parties in the past often included a large number of beaters who handled the dogs and flushed birds for the goshawks of the lords. From these excursions, porters returned laden with game. Although such opulence belongs to the past, the record remains to show us what can be accomplished by carefully trained hawks, and some of these techniques may be successfully applied today.

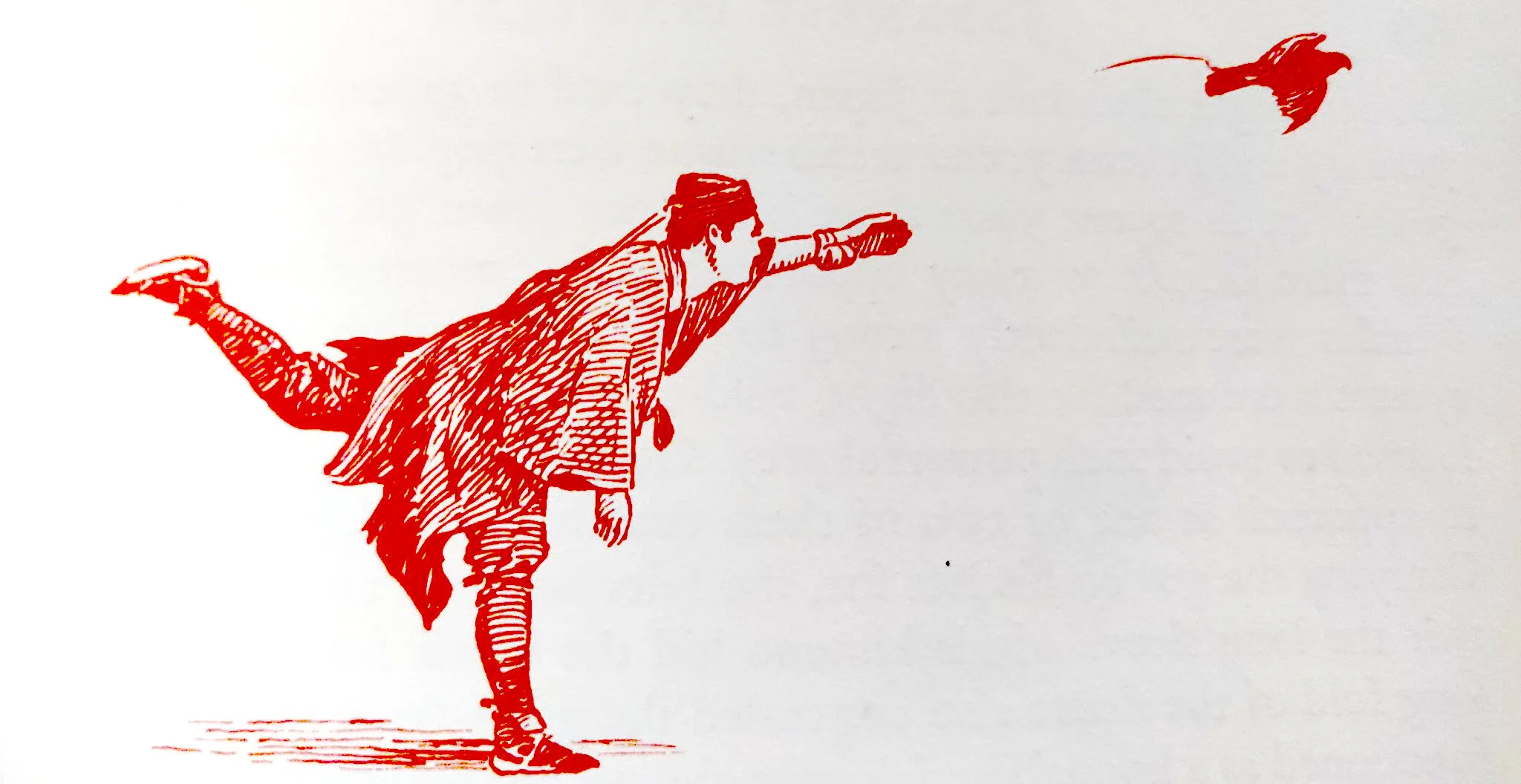

As elsewhere, falconers in Japan fly goshawks from the fist. It is the habit of some to adopt a special posture and thrust when releasing a gos: the left leg is placed in front of the right and, as the bird leaves the fist, the falconer lunges forward and pushes his fist in the direction of the quarry. Thus, as the hawk leaves the glove, the falconer's left arm is stretched out in front and his right leg out behind. Such aid can be given the hawk only when her actions can be anticipated. Goshawks in the past were trained to take hares, pheasants, ducks, and geese.

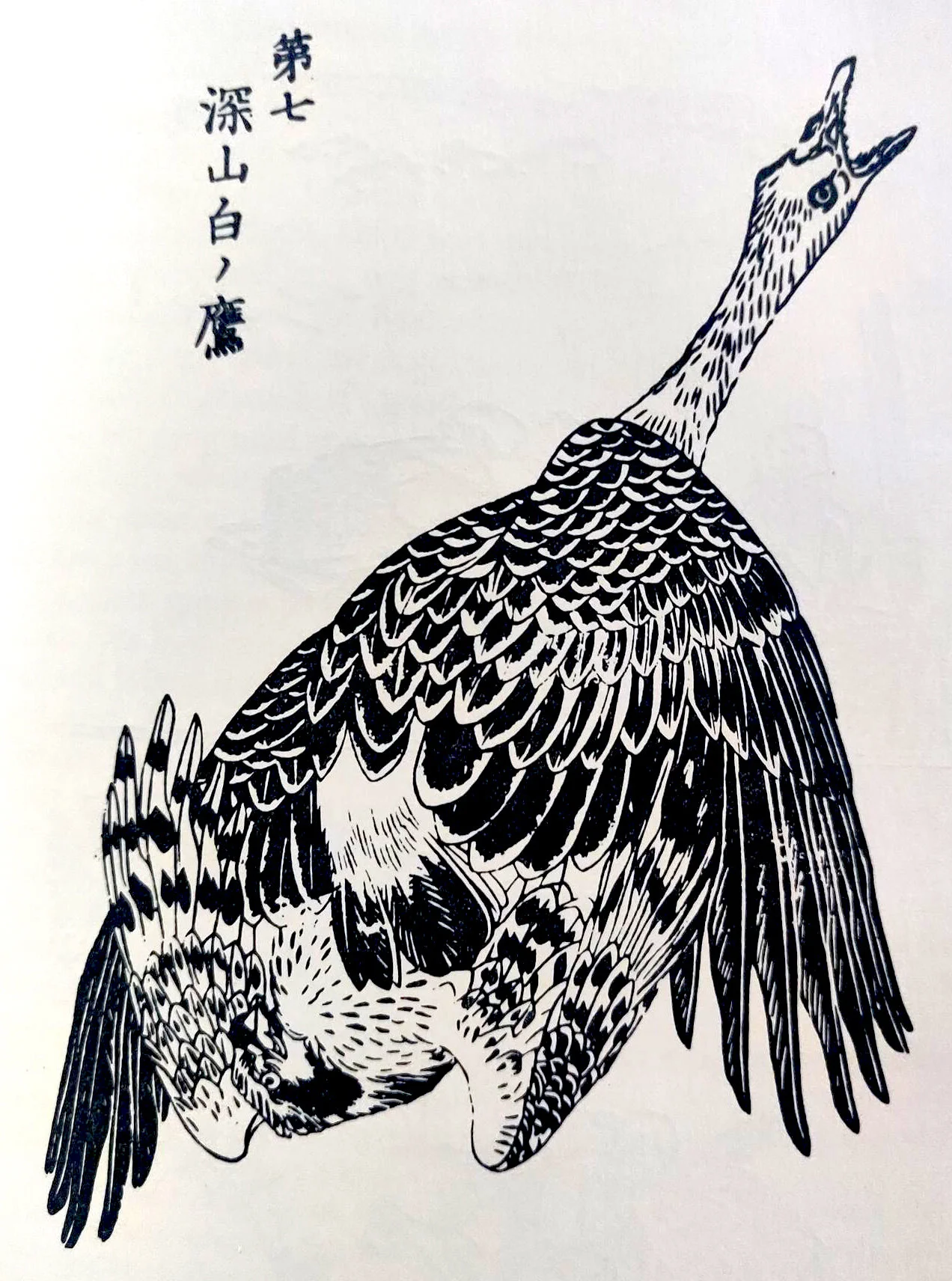

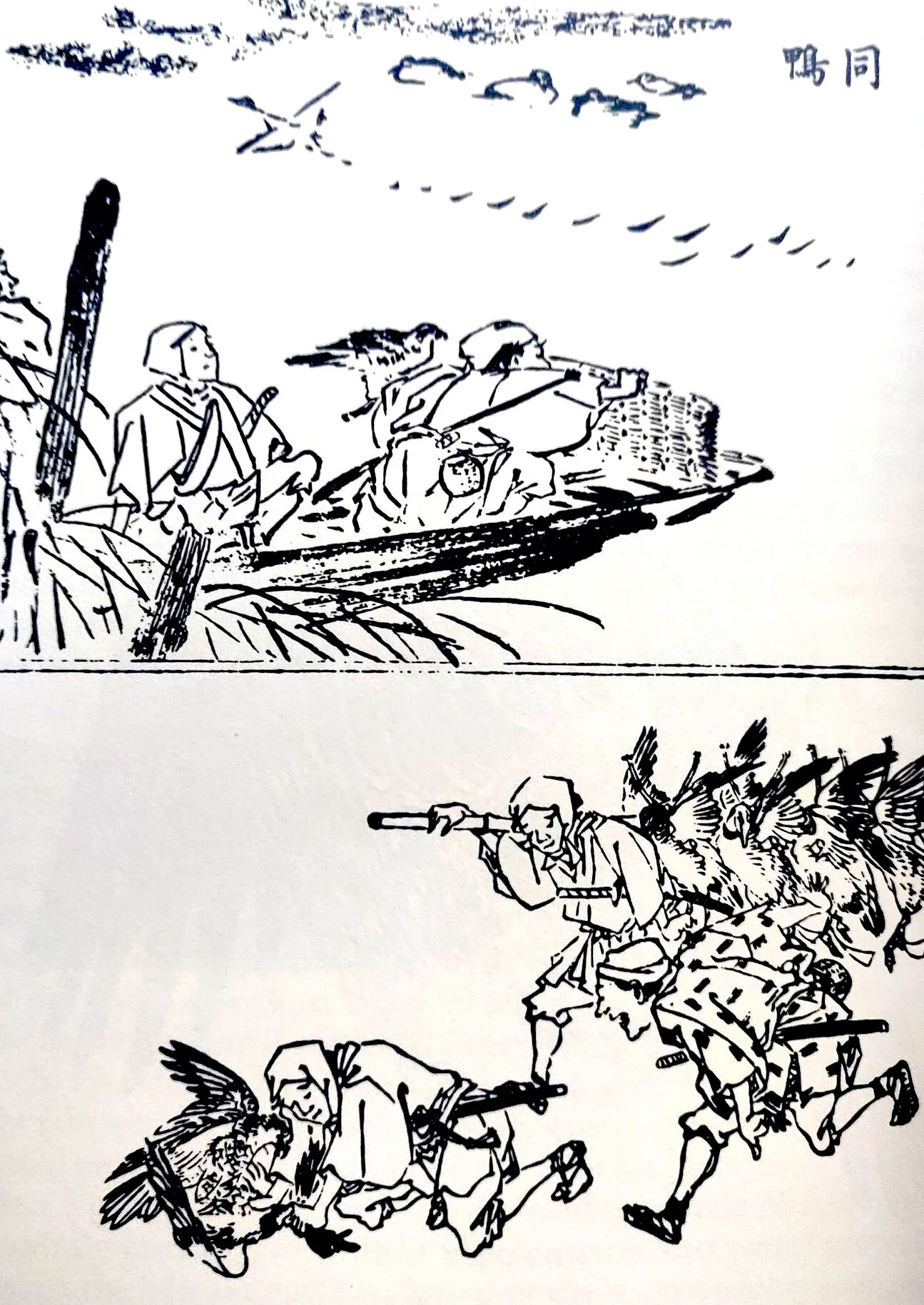

Flights at geese can be among the most exciting for the quarry is a strong one and is not subdued without some danger to the hawk. Snow, bean, and white-fronted geese were the species hunted. Although geese are no longer abundant in Japan, they used to appear in rice fields in January and February, and at this season were popular game for trained goshawks. In recent years there have been fewer geese visiting Japan, and there are not so many opportunities to capture these birds. Only females were sufficiently strong to hold a struggling goose and only eyasses were used for this flight, wild-caught hawks apparently having learned to avoid such powerful prey. Geese are very wary and difficult to approach as one or two of them continuously watch for enemies. Carrying the gos on his left fist, the falconer held up his right arm so that the long sleeve of his kimono hid the hawk from the geese; the long fold of the sleeve also concealed the geese from the hawk and so functioned as a hood. The falconer always hunted geese with an assistant as the birds were especially wary of a lone person afield. The pair walked back and forth, zig-zagging in front of the feeding geese, slowly approaching so that the quarry were unaware of the decreasing distance. Moving slowly into the wind, the two men could come to within about twenty or thirty meters of the geese, at which point they would begin to cluster together. Then the hawk was released. When the hawk bound to a goose, the two birds dropped to the ground, flapping and fighting, where upon the remainder of the flock returned to assist its comrade. In contrast to the custom in some western countries, the austringer made in to his hawk with the greatest haste. The speed of the falconer was then of utmost importance for the geese could quickly beat to death the solitary gos. The falconer in one act protected his hawk and assisted in the end of the prey. Consumed with the excitement of the tussle, a hawk, at this moment, is not alarmed by the onrush of the austringer, and is not likely to carry.

To take ducks the gos needed a good start, and to accomplish this the falconer had to approach this wary quarry unseen. Sometimes ducks could be enticed into small, steep-sided ditches by repeated baiting and, after a period of days, the falconer could be certain of finding waterfowl. By placing grain in areas which were at least partly protected by cover, the falconer could walk to near the water's edge unseen, and get his bird in the air soon after the ducks had flushed. Ducks on open water could be taken by a goshawk when the falconer hid in a floating blind. In a small boat concealed by a cover of reeds the falconer and his bird floated slowly downwind, toward a feeding flock; and when close, the hawk was slipped (Fig. 17).

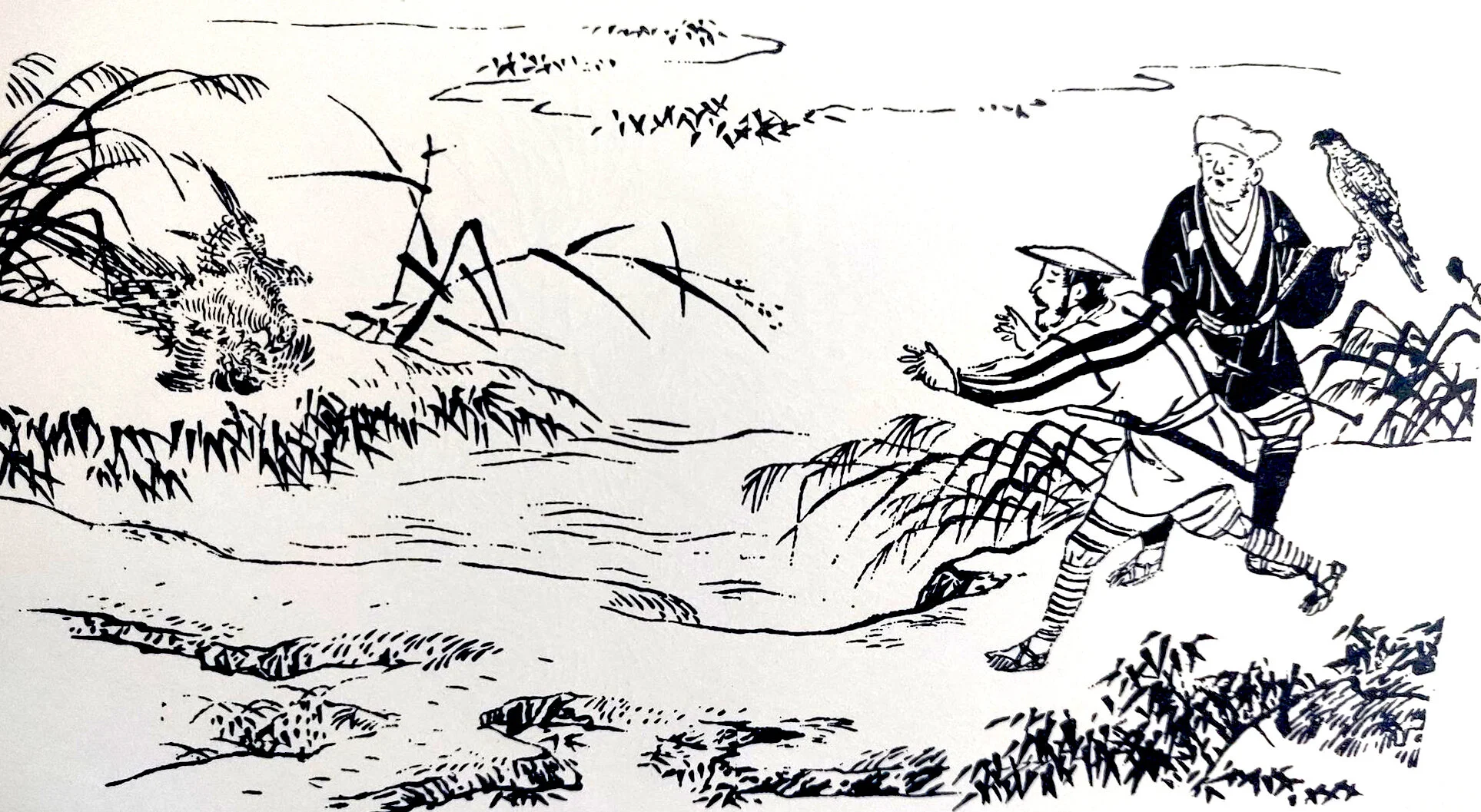

Pheasants were a popular mid-winter pursuit (Fig. 18). Because of the uncertain flush of pheasants, this flight was not such a carefully planned attack. The falconer could go alone or use assistants to drive the pheasants to flight. Dogs were used, any small breed with a good nose being acceptable. It was essential that pheasant dogs be taught to sit immediately upon the flush of the game, for frequently the hawk feared the dogs; and if the dogs chased the pheasant, the gos was likely to be badly frightened. If a good bird, the gos will not give up, but will follow her prey until it puts in to cover and then sit and wait on the follow her nearest high perch. From her point of vantage, the hawk is likely to tie in to the pheasant as soon as it is flushed by the falconer; and even should the hawk fail, the quarry will soon be exhausted and terrified.

Excellent sport is provided by a hawk and a dog which know each other. The bird soon learns to interpret the behavior of a reliable dog and will follow it until their game is put up in the air. Usually a bitch was used. As with the goshawks themselves, trained dogs were first brought from Korea and later they were trained in Japan. Initially dogs were trained with sparrows and then were graduated to quail. When proved dependable in the field, the dog was taken out with the hawk. The dog was then trained to walk to the right and slightly in front. An old Japanese proverb, inu hone hotte, taka ni tora waru, means that a dog digs up a bone which is taken by the hawk. This expression, now used for comparable situations in modern life, dates from the days when the working of a dog and a hawk together was a familiar relationship. The Tokugawa Period of Japan produced many such expressions; and, in this sense, may well correspond to Elizabethan England, from which we have many common phrases as leftovers of hawking.

In ancient times ducks were decoyed by a specially trained dog. The dog was selected for its red color and fox-like appearance, and was taught to decoy waterfowl. Sitting on the bank of a pond, the dog became the object either of curiosity or anxiety, and the ducks approached. The falconer hid behind a blind and when the quarry was close, he slipped the gos from an easy distance. This required an unusual high degree of cooperation between the dog, on the one hand, and the gos and falconer, on the other.

The copper pheasant (yamadori) was not at any time regularly caprured by trained goshawks; either these pheasants are too fast, or live in cover too thick for hawking.

Other species were occasionally pursued with gosses. The most formidable quarry was the crane, once common throughout Japan. A crane is not only a dangerous antagonist, but a wary creature that required careful stalking and attack. To place the hawk close enough for a flight, the falconer hid with the gos in a blind near where cranes were known to feed. The prospective prey was baited and grain was concentrated near the blind. When a crane wandered close to the falconer, he slipped the hawk and then hurried to assist her. If a hawk took a crane, the falconer received a gift of gold from the daimyo and the assistants were also rewarded. It was the custom for the falconer to present the crane to the daimyo; and, in his presence, cut open the left side of the bird and feed the liver to the hawk. Egrets were also hunted, the hawk in this case sometimes adopting a special attack. Egrets, in the past as now, were frequently found in rice fields and could be located with little difficulty. For an egret, the hawk was slipped at a distance and, hiding herself by a row of trees or shrubs, she flew unseen until close to the egret. As in the case of other quarry, egrets were held by the head, but for the long-beaker waders this was of great importance as these birds can quickly injure a goshawk with a stab of their long beak. Also, the gos sometimes managed to insert a claw between the upper and lower mandibles, thus disarming the egret.

In the past night herons were a legitimate game for the falconer's bag and even today, although all herons are protected by law, they are sometimes pursued by trained goshawks. Night herons are best sought on winter mornings, when they are resting, usually in the sun. Although these slow-flying birds are easily captured, they are a dangerous opponent for a goshawk and can use the long beak as a stiletto. Reputedly, the hawk attempts to place a talon between the heron's mandibles, rendering the quarry incapable of fighting back.

The hare is the only furred quarry regularly sought with trained gosses. The Japanese species (Lepus brachyurus) is a husky animal and is held only by a persistent and powerful hawk. The technique of pursuit is not a special one, but usually many beaters were used. To hold a hare a hawk must be strong and in fairly high condition. In addition, if a bird was to be trained for hare hawking, its talons were sharpened with a knife so that each talon was chisel-shaped; that is, the flat plane was transverse to the pressure upon the claw. Each claw was cut just until the blood flowed, and the bleeding was stopped with a hot iron.

Coots and gallinules were, and still are, hunted in May and June in Honshu. Although the season is short, one gos can capture forty or fifty birds per day. In ancient times, when the lord could recruit any number of beaters, a falconer used five or six assistants, but these birds can be hunted without helpers, even without a dog, and the coot is one of the few birds still available to modern austringers. In Japan, as elsewhere, the coot is considered to be an easy quarry and the hawk seldom fails unless the coot takes to the water.

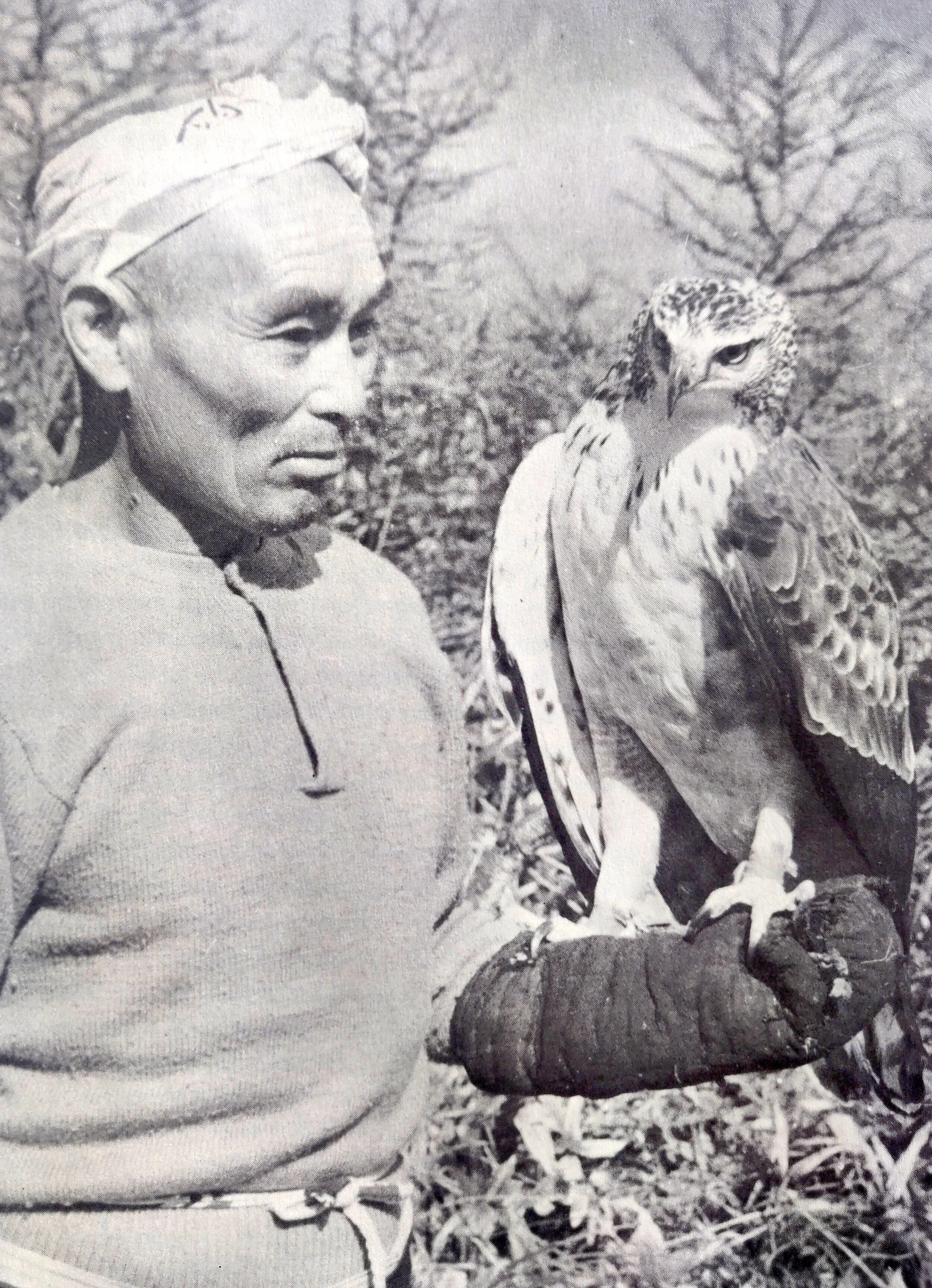

Hunting with the hawk-eagle differs somewhat because of its larger size and the nature of the quarry. The following discussion is essentially that explained to us by Asaji Kutsuzawa, although we have drawn from conversations with other falconers who have trained these birds, especially Toshio Tomita.

If properly entered with the stuffed hare skin, the kumataka will readily chase the wild quarry when encountered in the field. With the proper training and a sharp appetite, the bird is prepared for hunting.

Before going afield for the first time, it is necessary to remove the acute points of the middle and hind claws. These claws are filed at their tips so as to dull them just slightly, and then they are burned to temper them to hardness. Great care is taken in filing the tips, lest they bleed. When the hawk sights its quarry, it grips the glove with excitement, piercing the leather if the claws are not slightly dulled, and this may delay the hawk's departure after game.

The removal of the kumataka from its freshly-caught quarry is done in a special way. After the game has been killed, the falconer approaches his bird and, squatting down in front of it, gives it a piece of meat from the food box. He then grips the bird's legs just above the feet; and, when the bird straightens its legs, the trainer places one foot on the quarry and gently lifts the hawk onto his fist. Of course, this must be done by the falconer, for the hawk would resent such an action from a stranger.

In hunting the falconer walks with his bird along a ridge or hill if possible for the greater height will give the hawk a distinct advantage, as these hawks are definitely in a weakened condition when flown. This higher elevation will improve the sport. If the game is higher, it will see the hawk easily and the hawk will have difficulty in attaining the level of its intended quarry. Even if there are lots of trees and bushes, there is no need to worry because the kumataka can see very well. The falconer must consider the weather and temperature when trying to locate a hare, especially when judging where the hare may be sleeping. When the sleeping hare is located, the falconer places himself in the most favorable position for the effective stoop of his hawk-eagle. The bird's excitement will indicate that it has sighted the hare, and instantly the jesses must be released. When it has killed the game, it will cry "peee, peee" until the falconer arrives. The hawk will remain with its prize, but generally will not eat it. Sometimes when hare hunting, the game is started and, while the hawk is in pursuit, a fox joins the chase. Then the hawk turns on the fox. This is an anxious battle for the falconer because the fox is a savage and powerful quarry.

When hunting in the mountains, a hawk-eagle may disappear from sight and it is then very difficult to locate. Usually, however, if a hawk-eagle has not succeeded in overtaking its quarry, it will return when the falconer calls to it. If the bird has killed, and the falconer does not find it, it may proceed to eat its prey, in which case the falconer must return early the next morning and, where he lost his bird, he will hear it calling, "Peee, peee."

One may hunt from a fixed position, waiting on a high hill with the hawk on fist, while below drivers beat the cover in order to force the game to go beneath the hawk. The bird must be slipped as soon as the quarry moves. This method sometimes produces excellent results, depending upon the locality and the abundance of game. When using beaters, crusty snow is a great help.

When there is no snow, dogs will greatly assist the falconer in finding the retiring hare. They are especially useful in regions of very dense undergrowth where it is difficult to see the quarry and also awkward for the hawk to chase it. The hawk and dog must be trained together and must be completely friendly at all times. The dog will show respect for its winged ally, but a large dog must be employed, for a kumataka will attack terriers and other small dogs. When at home, the dog and hawk must be near each other and they will learn that they are part of the same family. When the two are hunting as a team, the dog routs and chases it into the open where the hawk can stoop. The 75 the game bird is then released and leaves the falconer's fist.

Marten (Martes melampus) can be taken with a hawk-eagle if the falconer can locate tracks in the snow. Sometimes the trail will disappear in a grove of trees and then the falconer must find the nest tree where the marten is sleeping. By knocking on different likely trees (old trees with holes or broken snags) the falconer may rout the quarry, and then the hawk will fly from the fist.

Pheasants are too fast to be caught by a hawk-eagle in straight flight, but in winter this quarry frequently seeks cover and escape in a snowbank, and then the falconer can reach in and grab it with his hands.

Hawk-eagles are able to capture pond ducks such as mallards and pintails if the quarry is spotted on the water. Mr. Toshio Tomita, of Tokyo, has taken ducks in this fashion with a male hawk-eagle.

As mentioned previously, clear weather is the finest for hawking. It is best on a bright sunny morning after a fresh snowfall. The tracks are easily seen in the fresh snow and the hares will not move far, so such conditions are most auspicious. On the contrary, if it snows during the day and clears at night, hunting is difficult. In years of deep snow, hawking is most successful for then the bushes and small trees are buried and the hawk can dive easily. Strong winds are to be avoided, but if the hawk is flown at such times, effort should be made to make it possible to slip the bird downwind. Hawks do not like to pursue their prey upwind, and probably will not do so for very long.

The pursuit may take a variety of turns. If the bird fails in its attempt and the hare takes cover under a bush, the hawk sits nearby in a tree, and will wait for the falconer to drive out the quarry. Or, if other hares are nearby, the hawk may pursue another. If the hawk carries his quarry into a tree, it is in too high a condition; and, if this happens, it will not return to the falconer. Great care must be taken to see that the bird is sufficiently strong but not overfed.

The kumataka is not friendly to others of its own kind and two of these hawks cannot be flown together. Two falconers, each with a hawk-eagle, may hunt together, taking care, of course, not to slip both birds at the same hare. When two are taken afield together, one falconer walks along a ridge, and the other downhill. In this way, if a hare runs out of a gully or ravine, the lower hawk will chase it, and if the prey goes uphill to escape, the higher hawk may be slipped. In this case, before the upper bird is flown, the lower hawk must be taken up.

In hunting, these birds are powerful and brave, and demonstrate that they are the true king among hawks. Their flight is strong, for they can carry away a full-grown hare or pheasant. When young, hawk-eagles are completely without fear and may dive into cover with such force as to hurt themselves, but with age and experience, they become more skillful and wait for the most appropriate instant for striking.

The manner of clutching the quarry is important, especially in the case of formidable enemies such as foxes and raccoon-dogs. The method of holding hares varies among individual birds: some will grab the head and others will bind to the loin. When attacking dangerous game such as badgers, raccoon dogs, and foxes, the kumataka must be both cautious and bold, and for these creatures the hawk has a special technique. From above and behind, the bird grabs the prey by the hindquarters and back with both feet, and as soon as the prey turns its head, the bird clutches the jaws with one foot. The hawk then holds the enemy powerless. The skill and effectiveness of this method are magnificent beyond description. If the hawk fails in its first attempt to seal the muzzle of the fox, he will then hold the fox's head with both feet, in which case it will have difficulty in preventing the mammal's jumping about. If the bird cannot grip both the head and loins of the fox, he will have great difficulty in killing the prey by himself. The bird may sometimes be killed unless the two combatants become separated. The hawk well understands the danger of its quarry and also knows its vulnerable points, but, nevertheless, the moment of the dive is a tense and anxious one for the falconer.

Mr. Asaji Kutsuzawa offered the following advice to one desiring to train a hawk-eagle. "The critical talent of the falconer is very important to the success of the hunting, but one cannot acquire this without long years of experience. Naturally, one must learn the traits, habits, and distinctive behavior of each hawk. One must also learn to appreciate the response of quarry the to weather and temperature. For example, when you see the footprint of a hare in the snow, you should be able to tell where it came from and where it sleeps. In this way you can learn the close relationship of the quarry's habits to its environment."